GROWING FOOD SECURITY

Donation gardens blossom to fill urgent needs

By Coleman Cornelius

March 15, 2021

GRADUATE STUDENTS HUGO PANTIGOSO and Savannah Hobbs have regularly relied on the Colorado State University food pantry to fill gaps in their grocery needs.

Last summer, they gave back just as the COVID-19 pandemic was fueling hunger and food insecurity nationwide: The students grew more than 2,000 pounds of fruits and vegetables for others who depend on the campus food bank.

“It’s amazing to harvest that much produce,” Pantigoso said, as he checked ripening tomatoes at the tail end of the growing season in late September. “It’s great to be able to give back. It feels good.”

Pantigoso and Hobbs led a pilot project at CSU’s Agricultural Research, Development, and Education Center to ease food shortages, which have starkly worsened during the pandemic. With just a few other volunteers, the two planted cucumbers, peppers, squash, tomatoes, and watermelon in four 300-foot rows, covering one-fifth of an acre at the research farm just east of Fort Collins. They tended the plot through the growing season, harvested produce on the weekends, and donated it to the Rams Against Hunger food pantry for distribution to CSU students, faculty, and staff in need.

“I saw the importance of Rams Against Hunger because I have relied on the food bank and have seen the good it’s done in my life,” said Hobbs, a doctoral student in food science and human nutrition. “It’s very powerful to think of helping other students in that way. We’re excited to make creative use of existing university resources and to keep this project moving and growing.”

Savannah Hobbs, a doctoral student in food science and human nutrition, helped lead the pilot project to grow produce for CSU students facing food insecurity. Photo: Mary Neiberg

By late summer, the fresh fruits and vegetables from ARDEC South – grown in an open corner of the research farm – had helped hundreds of other low-income students. Rams Against Hunger distributed the produce along with nonperishable staples.

“It’s rewarding to see a small piece of land producing this much nutritious food,” Pantigoso marveled, scanning rows at the CSU farm.

An agronomist from Peru, he came to CSU to pursue a Ph.D. in horticulture and to conduct research into the interactions of crop roots and soil organisms, which could lead to new biological technologies that reduce the need for synthetic fertilizers. In the process, Pantigoso helped launch the first-time food project to support other students struggling to buy groceries with minimal income. At the same time, the budding project is designed to teach the basics of farming to student volunteers without agricultural backgrounds, thus increasing food literacy along with food security.

Hugo Pantigoso is a CSU graduate student in horticulture who helped start a donation garden at a university research farm east of Fort Collins. Last summer, the student-led project grew 2,000 pounds of produce for distribution to CSU students through the Rams Against Hunger food pantry on campus. Photo: Mary Neiberg

The ARDEC South Food Security Project sprouted when a small group of students, faculty, and staff connected the dots between campus food needs and university resources. The CSU farm has previously donated produce grown in the course of conducting research; for instance, while studying the hardiness of crop varieties or the effectiveness of irrigation techniques. This time, the fruits and vegetables were planted just for donation, with volunteer time dedicated to harvesting and distribution – laborious tasks that often take a back seat at a university research farm because of limited staffing.

The ARDEC South project is one of several CSU farm-to-food bank efforts that have harnessed the land-grant university’s collective ingenuity, community networks, and agricultural resources to help solve the longstanding problem of food insecurity, which has dramatically mounted during the pandemic. Together, the programs illustrate how even small-scale coordinated efforts, powered by volunteerism, can put a dent in significant local problems.

The COVID-19 crisis has compounded hunger and food insecurity among low-income individuals and families nationwide, a dire ripple effect of economic upheaval, unemployment, and market disruptions. More than 50 million people, including an estimated 17 million children, faced food insecurity in 2020, according to a recent report from Feeding America, the nation’s largest hunger relief organization. That was a spike of 35 percent in the U.S. population overall and of 50 percent among the nation’s children, compared to rates before the pandemic. It means nearly one in four children hasn’t had enough nutritious food for good health during the pandemic, and their families have been unable to buy it.

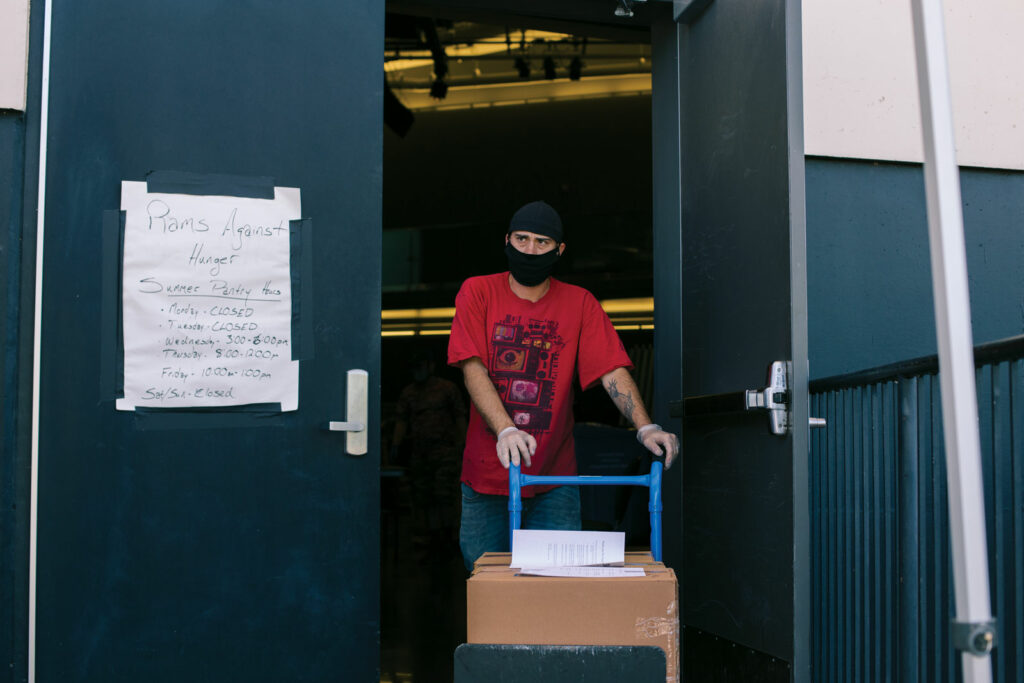

Food insecurity has spiked among financially stressed students, prompting the Rams Against Hunger food pantry to expand significantly: Before the pandemic, it operated once a month on the Fort Collins campus; now, it is open three days a week. Those who visit the pantry receive boxes filled with staples and fresh vegetables. Photo: Ben P. Ward / Colorado State University

Two principal branches of the state’s land-grant university – the Colorado Agricultural Experiment Station and CSU Extension – have taken a lead in tackling food insecurity. With research centers and outreach offices in communities across Colorado, the two university agencies are uniquely equipped to help.

For instance, the Colorado Master Gardener Program, a well-known Extension offering, launched Grow & Give, a statewide project motivated by the pandemic and modeled on backyard victory gardens that boosted food supplies and morale during the bleak years of World War I and World War II.

Grow & Give struck a chord: Nearly 600 gardeners volunteered last summer; they raised and donated almost 50,000 pounds of fruits and vegetables to charitable food programs that serve people in need from the Western Slope to the Eastern Plains. That’s 25 tons of fresh produce, from beets to beans and leafy greens.

“Many of our volunteers were asking, ‘What can we do that will really make a difference?’” said Katie Dunker, statewide coordinator for the Colorado Master Gardener Program, who helped lead Grow & Give. “Instead of opting out of programming in such a strange and difficult year, we said, ‘Grow with us.’ This is where CSU Extension can make such a big difference connecting people to solve real needs in their communities. It took a pandemic for us to see all this capacity, but we’re going to continue this work. It hits all the marks for a land-grant university.”

Other CSU programs, both well rooted and newly bloomed, have joined in. For instance, the San Luis Valley Research Center, part of the Agricultural Experiment Station in southern Colorado, donated 48,000 pounds of potatoes grown while testing varieties and farming methods. The Southwestern Colorado Research Center milled grain from a portion of its wheat crop and donated 525 pounds of baking flour to food banks in the Four Corners; an Extension team in the region provided truckloads of apples from a CSU orchard.

“The silver lining that came out of the pandemic is we now have connections to all our local food banks and food distribution agencies,” said Greg Felsen, Montezuma County Extension director, who led the apple contribution.

The Community Alliance for Education and Hunger Relief, a program begun in 2017 at the Western Colorado Research Center near Grand Junction, is a model that has offered information and inspiration for other university efforts. The Community Alliance involves CSU staff, local schools, nonprofits, dozens of volunteers, and college students. Together, they grow, harvest, and distribute fresh nutritious produce from the research center to people in need, while simultaneously providing public education about food insecurity and healthy eating.

During the 2020 growing season, the program donated 76,000 pounds of fresh fruits and vegetables to charitable food outlets on the Western Slope. The bounty included apples, peppers, squash, tomatoes, and more – the kind of nutritious produce that’s often scarce at food banks. During four years, the Community Alliance has grown and donated a grand total of almost 350,000 pounds of produce, Amanda McQuade, program coordinator, said. That’s 175 tons of fresh food.

Left: Michael Buttram picks up produce for distribution through the Rams Against Hunger food pantry. Below right: Graduate student Hugo Pantigoso and farm manager William Folsom survey a vegetable plot at the Agricultural Research, Development, and Education Center east of Fort Collins. Photography: Mary Neiberg

Top: Michael Buttram picks up produce for distribution through the Rams Against Hunger food pantry. Bottom: Graduate student Hugo Pantigoso and farm manager William Folsom survey a vegetable plot at the Agricultural Research, Development, and Education Center east of Fort Collins. Photography: Mary Neiberg

“I love seeing other projects around the state gaining traction,” said McQuade, who has been a guiding force for university food security projects. “We’re directing site-specific CSU resources at community problems. The success of these programs tells me there is a lot of latent energy within the staff, students, and volunteers at CSU to respond to food insecurity.”

Just as it has surged in society broadly, food insecurity likewise has intensified in campus communities. At Colorado State in Fort Collins, demand is so significant that Rams Against Hunger expanded its food pantry from a monthly offering to three days a week. During fall semester, the campus food bank served more than 300 students, faculty, and staff each week, or nearly 1,500 people per month. That’s double the number helped before the pandemic, said Michael Buttram, who coordinates Rams Against Hunger. At CSU Pueblo, the Pack Pantry meets similar needs.

Buttram has worked closely with the ARDEC South Food Security Project to ensure its harvest reaches students, faculty, and staff. “This has been such a gift for the food pantry,” he said, while picking up several crates of late-season produce from the Fort Collins research farm. “Food insecurity was always a prevalent issue, but it’s become exacerbated during the pandemic. We have a sense of pride knowing we’re helping to meet that need with food grown at CSU for our campus community.”

Photo at top: Ben P. Ward / Colorado State University

SHARE