ANIMAL ATTRACTION

The virtual reality lab in Vida features a program that’s improving anatomy education worldwide.

By Coleman Cornelius | July 1, 2022

A GROUP OF FIRST-GRADERS RECENTLY SAT CROSS-LEGGED in the virtual reality classroom at CSU Spur. In moments, they would don VR headsets to explore the anatomy of dogs, cats, horses, cattle, and sheep. They would view real facial muscles, veins, and nerves. They would manipulate 3D images of an actual heart, brain, and lungs. They would see a sheep’s four-chambered stomach, a horse’s jaw, and a cow’s shoulder blade.

The kids were primed for the immersive lesson: They had just observed a dog’s neuter surgery at the Dumb Friends League Veterinary Hospital in the new Vida building at CSU Spur. With an educator narrating, the young students had raptly watched the procedure through expansive windows, with a close-up view of the surgery shown on overhead video screens. None of the children had flinched as they learned the surgery would prevent unwanted puppies – helping assure homes for other pets needing love and care.

Now the youngsters were ready to discover more about anatomy and its fundamental role in animal health and welfare.

“If you want to be a doctor for animals, you need to know about their behavior – that means how they act. You also need to know about the outsides of their bodies and the insides of their bodies,” Wade Ingle explained to the group. Ingle leads public education for Colorado State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences; he helps run the VR anatomy program at CSU Spur and takes it to communities around Colorado with a mobile lab. Ingle has introduced visitors ages 3 to 88 to the VR anatomy program in the Vida building at CSU Spur. “When you put on these goggles, you can check out the parts inside animals,” he told the first-graders. “Are you OK with seeing the insides of animals?”

Dr. Christianne Magee, an associate professor in CSU’s College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, leads the Virtual Animal Anatomy team that developed the software program in use at Spur. Photo: Mary Neiberg

They were, the kids affirmed with eager nods and squirms. Sure enough, with their VR headsets on, the youngsters felt like they were in their own darkened rooms, surrounded by 3D models of anatomical specimens, which may be moved and rotated with handheld controllers.

“I see a horse head, a brain, a belly, and a dog,” Analeigha Lucero said excitedly, after pulling on her headset and learning to use the controllers. She was with her class of 23 first-graders from Trevista at Horace Mann, an elementary school in north Denver. “This is pretty cool,” Analeigha said, as she used the VR program. “The horse is sticking out its tongue. The dog has sharp teeth – wow! Now, I found a heart.”

A little boy was equally absorbed. “I’m holding a leg!” Isaiah Rose exclaimed. “Whoa – I’m gonna get this stomach over here.”

Visitors can explore animal anatomy with virtual reality headsets and controllers in the Vida building at CSU Spur. Photo: Kevin Samuelson / CSU System

The students – 6 and 7 years old – took just a cursory spin through the VR program, which offers numerous anatomical views, quizzes, and detailed information about structures and their function. Still, seeing and repositioning even a few specimens in virtual reality would help the youngsters feel more confident and curious in their later science studies – and, ultimately, more interested in animal care, Ingle said.

A mom chaperoning the school trip agreed: “I’m sure at least one of these kids will leave today wanting to become a veterinarian,” Taresa Long said.

Nola Martinez, a 7-year-old, showed how that curiosity ignites. “This looks like a bone – I got it!” she proclaimed, as she manipulated the object with her controllers. “There’s the dog head. Here’s the horse head – eww, its teeth are dirty. I’m gonna move it right over here. And my bone, I’ll put it right over here. Now, let me grab my dog head.”

Little did the youngsters know, but the VR technology they used represents the future of animal anatomy instruction. The first-graders discovered anatomy with a software program tailor-made for veterinary students – and perfecting its use with virtual reality technology is one of the next big steps in the program’s development.

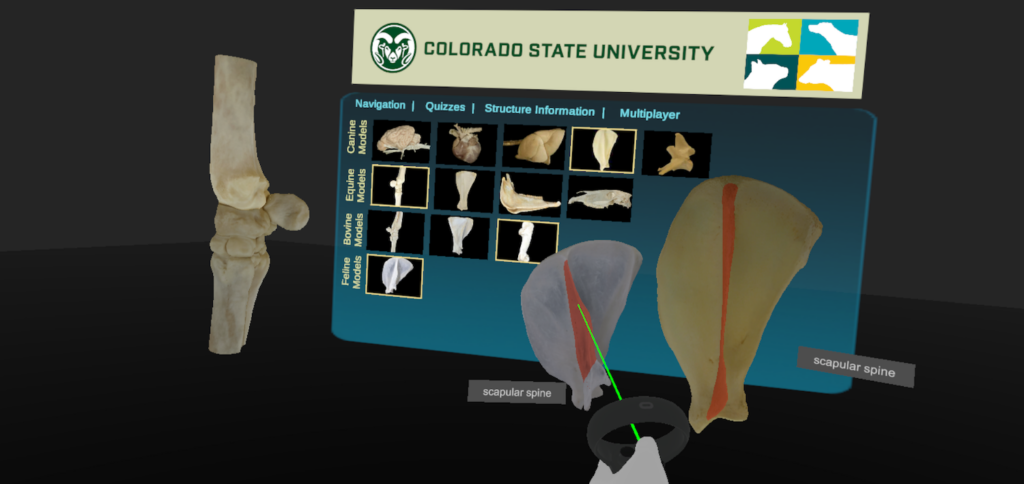

The VR experience at CSU Spur features computer software called Virtual Animal Anatomy. Developed at CSU, the program includes Virtual Canine Anatomy, one of the most widely recognized resources for teaching animal anatomy to veterinary students; it is helping to revolutionize anatomy education around the world. In 1999, faculty in CSU’s College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences began developing the virtual program for students enrolled in animal anatomy classes at the Fort Collins veterinary school. In the years since, the program has grown to include multiple species and has become a hallmark of the CSU vet school, which ranks No. 3 in the nation.

In the Vida building, visitors use virtual reality to explore anatomical specimens from dogs, cats, horses, and cows.

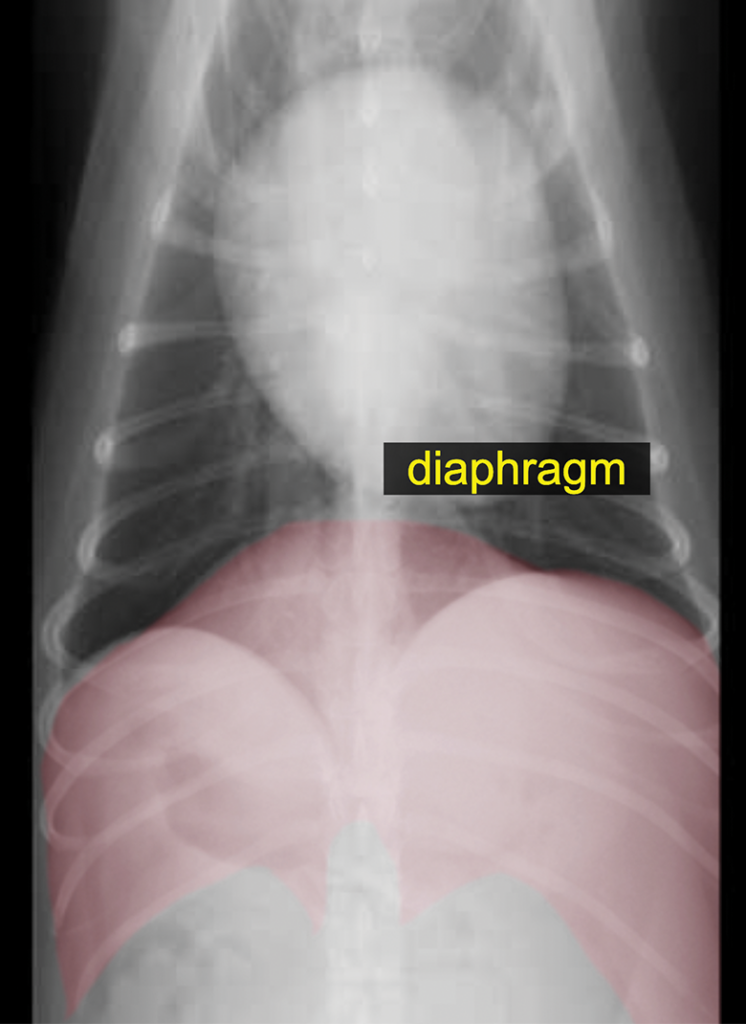

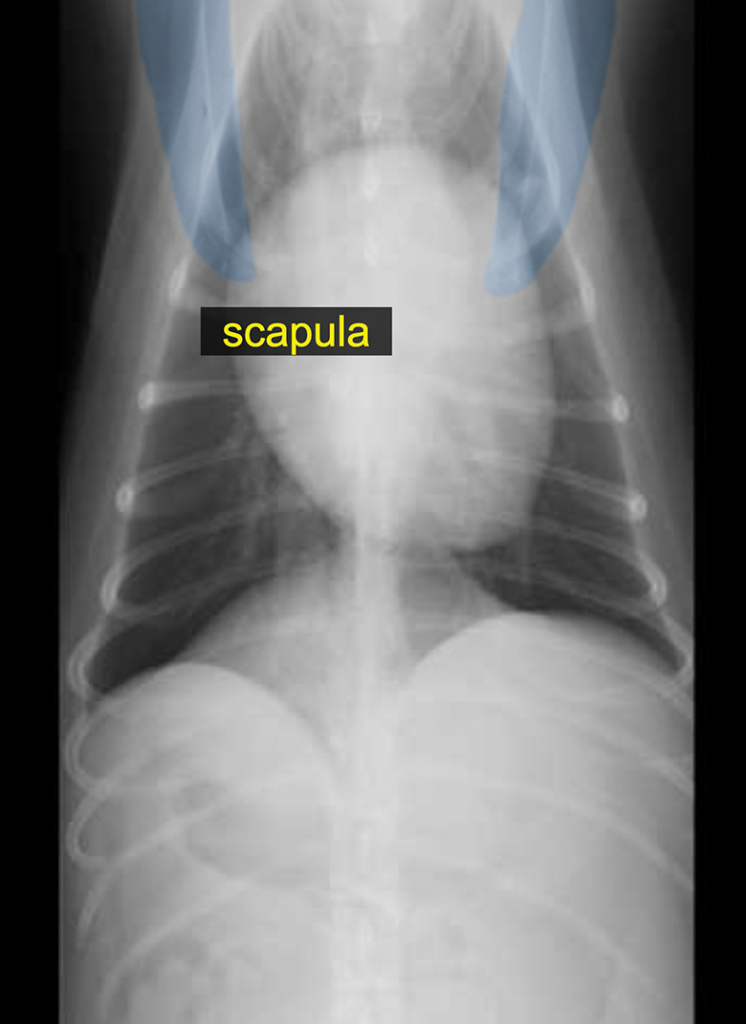

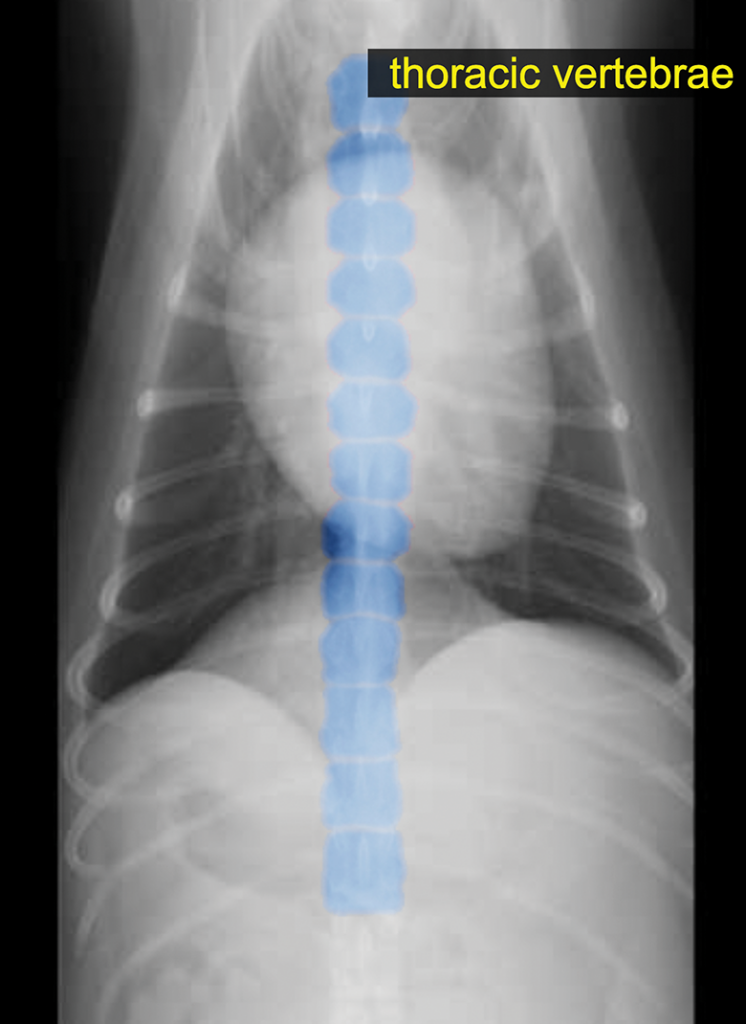

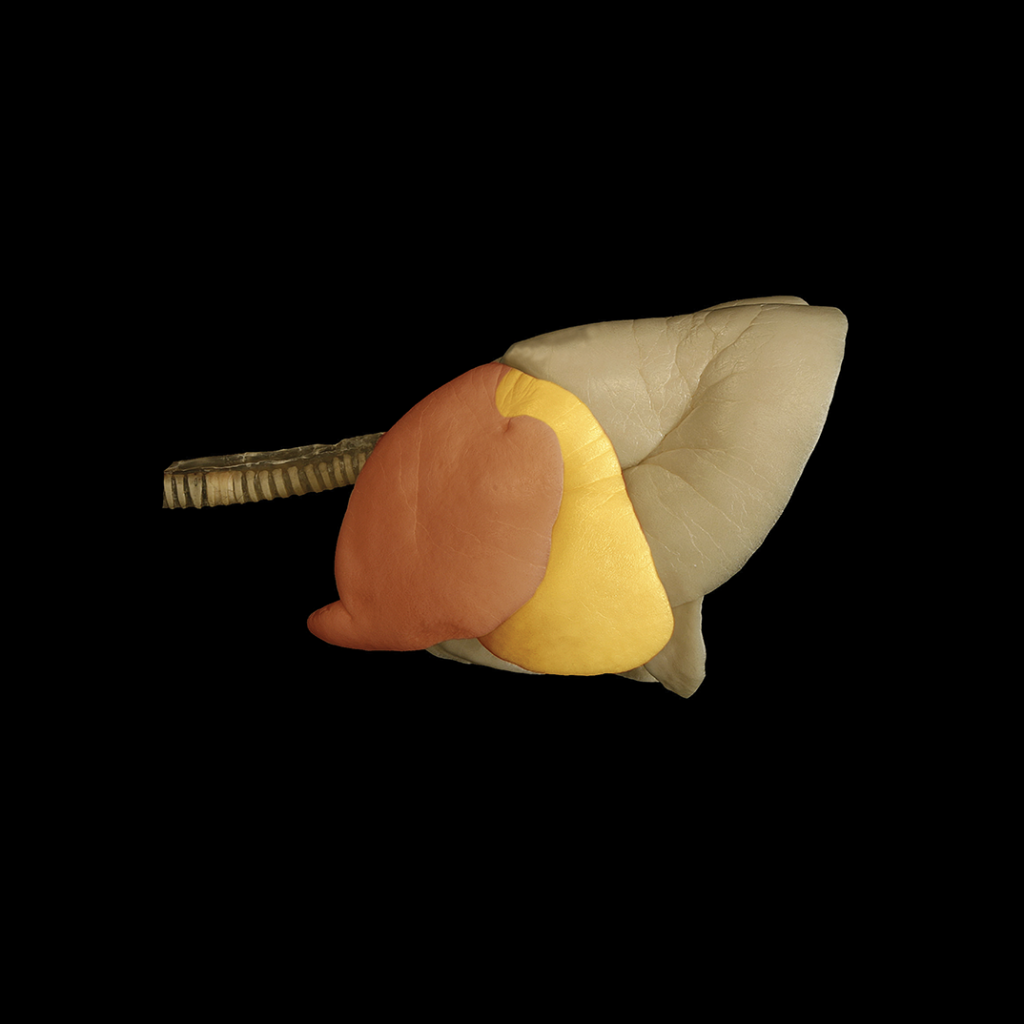

THE PROGRAM IS DISTINCTIVE FOR DETAILED PHOTOGRAPHY, revealing multiple layers of real anatomy in dogs, cats, horses, and cattle. Even the tiniest structures may be highlighted and identified, and specimens may be rotated so students attain views from multiple angles. It takes hundreds of hours to dissect, photograph, digitally piece together, and produce text for each interactive asset. For instance, 576 photographic images were stitched together to create the rotatable, multilayered model of a canine brain; the canine heart required 540 images, the head 323. In addition, the program provides quizzes, audio of scientific pronunciations, dissection videos, and written instructions to deepen learning and guide students in their laboratory work.

Exploring the program, it’s easy to see why veterinary anatomy courses are so challenging: There’s the sheer volume of information that must be mastered – and its importance to understanding and treating injuries and ailments. Let’s say a dog comes into a vet clinic with a deep gash in the side of its mouth, maybe from a fight or from digging through the kitchen trash and chomping on something sharp, like the top of a steel can. How would a veterinarian repair the serious cut, understanding placement and function of the buccinator muscle and the ventral buccal nerve that runs over the facial vein? What if the dog ate a sock – it happens! – or required treatment for a mast cell tumor, a common skin cancer? The health scenarios are vast, as is the anatomical knowledge needed among people entering veterinary professions.

“It’s a big necessity,” noted Andrew Garrett, a CSU anatomy instructor and content developer for the Virtual Animal Anatomy program. “When you’re trying to understand an animal and its health, you’re going to have to understand gross anatomy at some level.” (“Gross anatomy” is the branch of anatomy focused on visible bodily structures.)

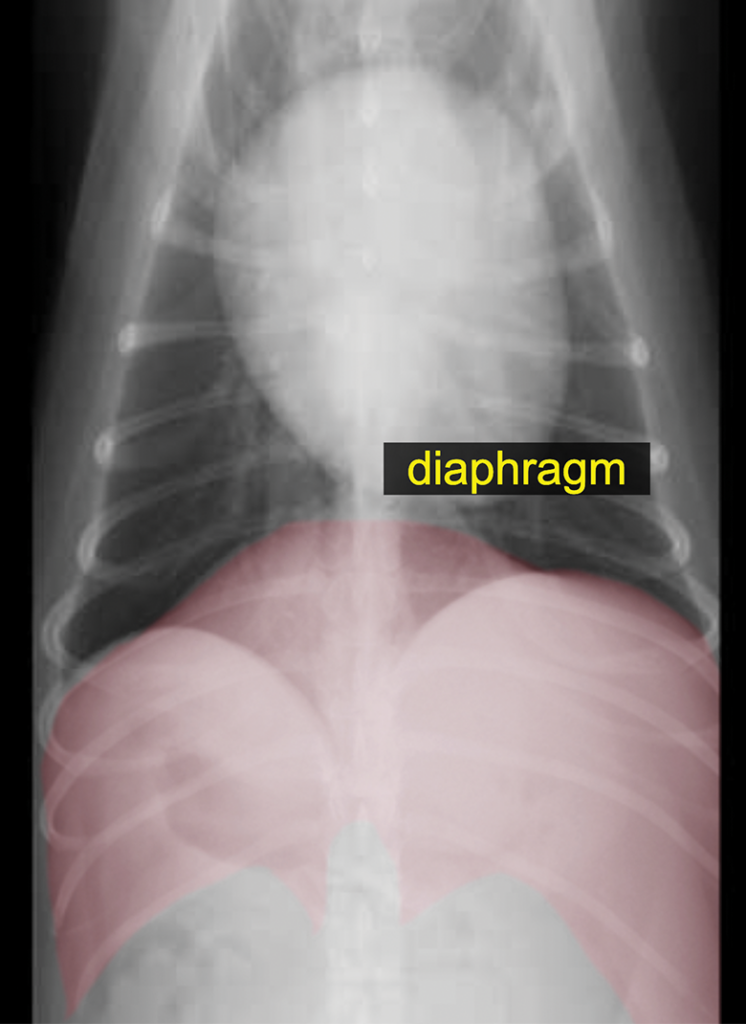

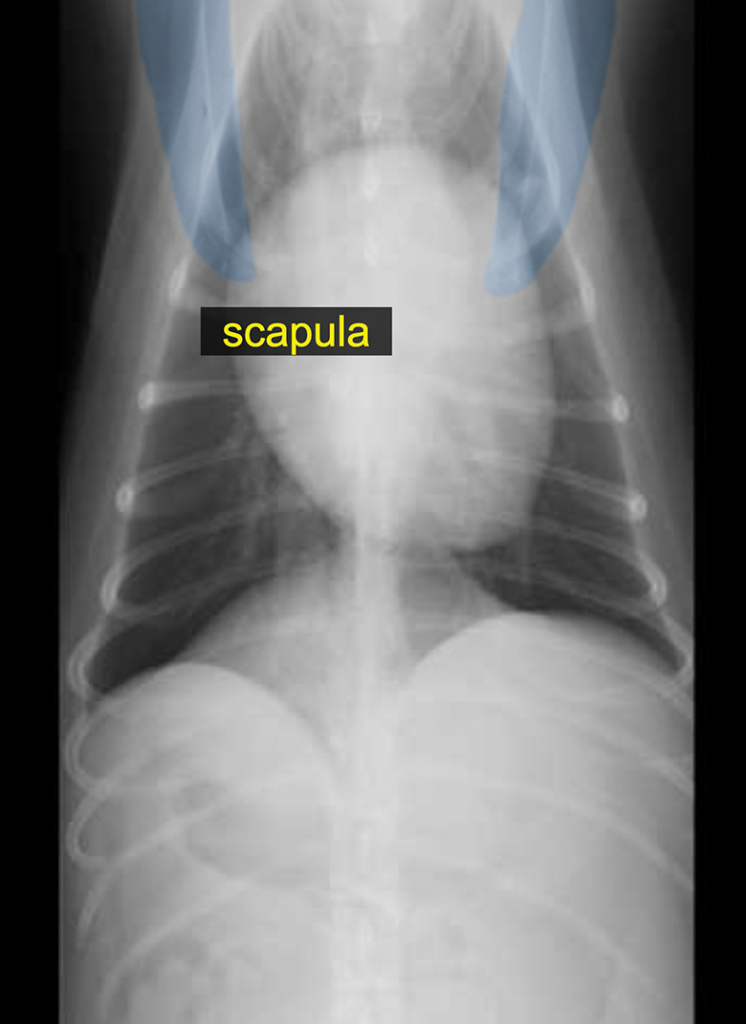

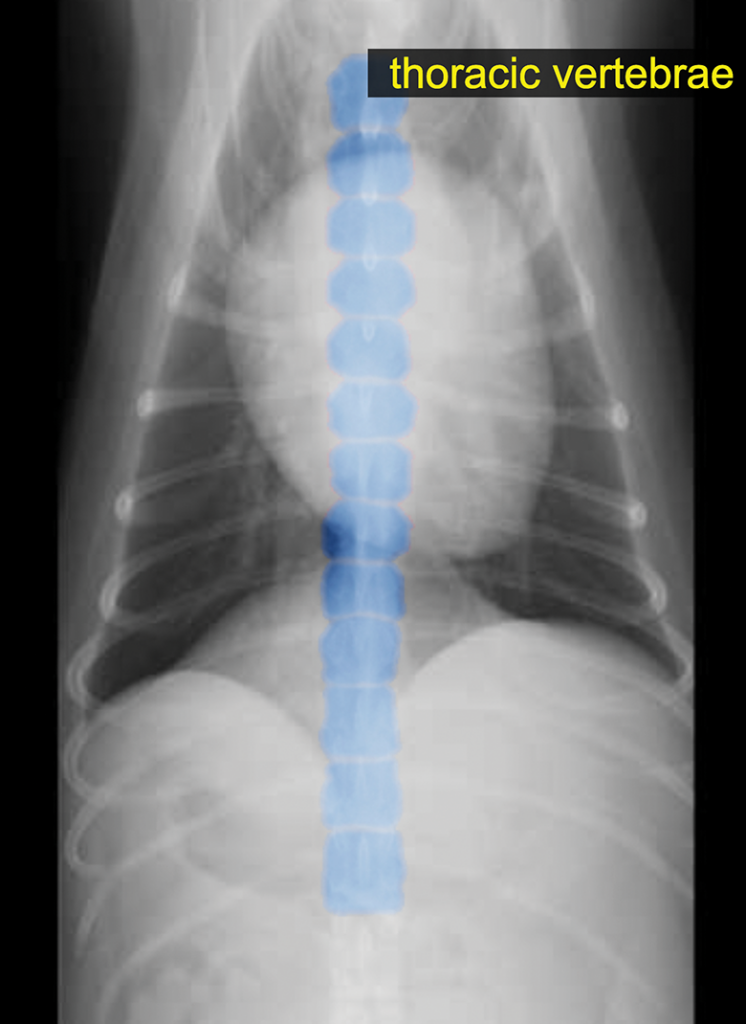

The Virtual Animal Anatomy program allows users to highlight and learn about specific anatomical features. At top, parts of a canine thorax are highlighted. Below, parts of a feline skull are noted; the red highlighted structures are, from left, the alisphenoid bone, occipital bone, and frontal bone.

The Virtual Animal Anatomy program allows users to highlight and learn about specific anatomical features. In the top three photos, parts of a canine thorax are highlighted. Below, parts of a feline skull are noted; the red highlighted structures are, beginning with fourth photo from top, the alisphenoid bone, occipital bone, and frontal bone.

WITH THE UNIQUE SOFTWARE, students have learned animal anatomy more efficiently, according to CSU studies published in scientific journals. As a result, they have relied on fewer animal cadavers, with more in-depth learning on those that are used for laboratory dissection, functional studies, and case-based discussion.

“Cadaveric learning remains such an important part of how we teach,” said Dr. Christianne Magee, a veterinarian and associate professor who teaches many CSU animal anatomy classes and leads development of Virtual Animal Anatomy. As Magee discussed the program, students in an adjacent laboratory gathered around dog cadavers to dissect and examine anatomical structures. “Our students expect us to have worked out what the best learning experiences will be,” Magee said. “The most important skill set we can give them is problem-solving and resource acquisition. So these technological resources are designed to both stand alone and to complement and support cadaver-based learning.”

The combination of Virtual Animal Anatomy and traditional cadaveric learning has been so successful that textbooks are now optional for some 400 students who take animal anatomy classes at CSU each academic year. The software program has not replaced textbooks and laboratory manuals, but it has grown into a heavily used tool for undergraduate, graduate, and veterinary students. “The more we put into this program, the less we see students buying textbooks,” Magee said.

Unlike visitors to the virtual reality lab at CSU Spur, animal anatomy students on the Fort Collins campus do not routinely use VR headsets to access the Virtual Animal Anatomy program. That is a likely next step in the program’s evolution. Instead, university students access the online anatomy program on their computers and use it on tablets for reference during lab sessions. The version used for course work is more extensive than that offered for visitors at CSU Spur.

“There’s a role for all these tools, and we need to understand what that is and how best to implement them,” said Dr. Jason Martin, a veterinarian and doctoral candidate who studies the use of virtual reality and other computer technology in anatomy education. Martin teaches animal anatomy at CSU and began working on the Virtual Animal Anatomy team while pursuing his master’s degree at the university. “The kids at CSU Spur are getting a glimpse into the future of anatomy education,” he said. “By the time they get to high school, college, and professional school, the resources they’re seeing now will be much more developed to enhance their learning.”

Cultures that care for animals care for people, so we can use this program to promote the interconnectivity of animal health and human health.”

— Dr. Christianne Magee, associate professor, CSU College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences

Alongside the software program, CSU has helped lead a nationwide change in the acquisition of cadavers for anatomy instruction: For decades, Colorado State has prioritized the use of donated animals for anatomy course work, rather than animals bred solely for that purpose. It’s a reflection of the university’s longstanding leadership in veterinary medical ethics.

With advances in Virtual Animal Anatomy, CSU faculty were well positioned in March 2020, when, in just one week, the COVID-19 pandemic forced courses to move entirely online. The university’s animal anatomy program already was there, and students already were adept at its use.

As the pandemic jolted campuses around the world, Magee got a flood of calls and emails from other schools seeking use of the Virtual Animal Anatomy program. The CSU Department of Biomedical Sciences, which administers anatomy courses, decided to provide free online access to the coveted program, which is hosted on a CSU computer server. A total of 148 institutions quickly began using CSU Virtual Animal Anatomy – benefiting 12,000 students worldwide. The program got so much global attention during the pandemic that Magee was invited to present information about it at the Summer 2020 meeting of the World Association of Veterinary Anatomists, the leading organization for anatomy educators.

Magee and her team spent that summer furiously building out the program with additional specimens. They completed a Spanish translation and updated the program for improved compliance with Americans with Disabilities Act website regulations. In response to requests, the team is also collaborating internationally to translate the program into Japanese and Portuguese.

At Colorado State University, students enrolled in animal anatomy take laboratory classes in this room, where cadaver dissection forms the core of learning. The Virtual Animal Anatomy program supplements this lab work; it has both improved learning and reduced the number of cadavers needed in anatomy instruction. Photo: Mary Neiberg

AFTER STUDENTS RETURNED TO IN-PERSON CLASSES, about 100 schools and individuals subscribed to the online anatomy program, with users in countries including Canada, Chile, Brazil, Ireland, England, Portugal, Israel, Thailand, China, and Japan. In the United States, users include not only high schools, colleges, and universities, but 4-H clubs and homeschoolers, said Andrea Linton, lead developer and instructional designer.

“It’s been a joy to have a vision and to have the ability to see the impact of it in teaching,” said Dr. Ray Whalen, a veterinary professor, neuroscientist, and anatomist who spearheaded the Virtual Canine Anatomy program more than two decades ago. From the canine unit, the program has expanded to include feline, equine, and bovine modules; its name changed to Virtual Animal Anatomy to reflect the inclusion of multiple species.

Whalen is a University Distinguished Teaching Scholar – a title granted to a select few CSU faculty members known internationally for instructional innovations – and he started Virtual Canine Anatomy to enhance anatomy education while reducing the number of cadavers needed for instruction. That reduction would be possible, Whalen reasoned, if students worldwide had a more effective resource to supplement laboratory dissections, which largely define college-level anatomy courses. This objective attracted program support from the Alternatives Research & Development Foundation, which promotes nonanimal methods in biomedical research.

A guiding ethic in Whalen’s teaching and research has been the Buddhist principle of “ahimsa,” or kindness and nonviolence toward all living things. “I’ve always wanted to value the full measure of an animal’s life,” Whalen said. He also has dyslexia and knows from personal experience that many students learn more successfully when advanced visuals and experiential discovery supplement written information and lectures.

The Virtual Animal Anatomy program features detailed photographs of specimens representing multiple bodily systems. Shown here are, from left, an equine upper forelimb bone, with the intermediate tubercle of the humerus highlighted; canine lungs, with the caudal part of the left cranial lung lobe highlighted; and a canine skull, with molars highlighted.

The Virtual Animal Anatomy program features detailed photographs of specimens representing multiple bodily systems. Shown here are, from top, an equine upper forelimb bone, with the intermediate tubercle of the humerus highlighted; canine lungs, with the caudal part of the left cranial lung lobe highlighted; and a canine skull, with molars highlighted.

With these perspectives, Whalen saw plenty of room for improvement in anatomy instruction when he started at CSU 40 years ago; his concept for the virtual program began to form. He envisioned the program as a digital atlas: Students could better prepare for their dissection labs, have a reference directing them through lab work, and later return to the photographic resource for review. “It would allow us to approach the material in a different way. It used to be that instructors would spend most of their time during anatomy labs going from one group of students to the next and identifying structures in their cadavers. ‘Yes, that’s the radial nerve. Yes, that’s the radial nerve. Yes, that’s the radial nerve,’” Whalen said. “The virtual program basically changed the relationship to focus more on function. So the instructor could say, ‘What if the nerve was damaged right here? What would occur?’”

To create the software, Whalen programmed at night. Many CSU anatomy students jumped in to perform dissections on the weekends. “Without the contribution of veterinary students, this program would have been impossible,” Whalen said. Even his children helped label and mail CD-ROMS, the format earlier used to share the program. For his work, the Colorado Veterinary Medical Association presented Whalen with the 2019 Distinguished Service Award.

In 2018, Whalen began transitioning to retirement and handed off leadership of Virtual Animal Anatomy to Magee; he continues to serve as a program mentor.

Now, the program’s use has expanded to the virtual reality lab in the Vida building. Kathryn Venzor, CSU Spur director of education, hopes to host middle school and high school students for anatomy lessons using the VR application. She envisions visitors observing surgeries at the Dumb Friends League Veterinary Hospital at CSU Spur, and then re-creating the procedures in the VR lab. “There are so many directions we could go with this kind of problem-based learning,” Venzor said. “It’s that idea of not teaching at people, but letting them experience what a veterinary team would experience.”

In university classrooms, Magee likewise sees multiple ways to potentially expand use of Virtual Animal Anatomy with the VR modality, guided by studies of instructional effectiveness. Until then, she’s excited that even the youngest students are experiencing anatomy in a new way at CSU Spur.

“Anatomy is in everyday life. ‘I bumped my elbow. What did I bump?’” Magee said. “My goal is that the kids at CSU Spur learn from the virtual program, that they have fun with it, that they get something out of it.

“We don’t have to use this program only to produce veterinarians,” she continued. “We have to create an educated populace that has the ability to care for the animal population. Cultures that care for animals care for people, so we can use this program to promote the interconnectivity of animal health and human health.”

COMING SOON: HUMAN ANATOMY

The virtual reality lab in the Vida building at CSU Spur features a program that lets visitors explore animal anatomy. Human anatomy is coming soon. Like the animal program, the human virtual anatomy program is a centerpiece of biomedical sciences education on the Colorado State University campus in Fort Collins. The human VR program started in 2019 as part of CSU anatomy offerings for undergraduates and graduate students, many bound for medical school. It has been called the largest deployment of virtual reality for medical education anywhere in the world. The virtual reality lab at CSU Spur is free and open to the public. For information, visit csuspur.org.

Photo at top: Radiograph of a dog intubated and monitored for surgery.

SHARE