STUDY SESSION

Weighing the risks and benefits of college degrees

By Anthony Lane | Jan. 1, 2023

Contributions from Cara Neth and Coleman Cornelius

THE GREAT RECESSION WAS OFFICIALLY OVER when Richard Deitz and a colleague at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York first calculated the payoff for a college degree. It was 2014, but the nation’s economy was still in the doldrums, and many college graduates were struggling to find jobs. A growing chorus questioned whether higher education was worth the time, trouble, and expense.

Deitz and fellow economist Jaison Abel gathered decades of data on college costs and employee compensation, then calculated the return on investment for the average college graduate over a typical professional life.

The ROI was consistently high: It had trended up from 1970 and settled at about 15 percent. By comparison, the historic rate of return on stock market investments is about 7 percent. Deitz and Abel published their findings in the Fed’s Current Issues in Economics and Finance. “With tuition rising, wages falling, and many college graduates struggling to find good jobs, the value of a college degree may seem to be in doubt,” the economists wrote. “However, these factors alone do not determine whether a college education is a good investment. Indeed, once the full set of costs and benefits is taken into account, investing in a college education still appears to be a wise economic decision for the average person.”

Students walk to and from class in the heart of the CSU campus. Photo: Joe A. Mendoza

Then, Deitz and Abel watched as college costs continued to creep up. They repeated their calculations five years later, in 2019. The return on investment in a bachelor’s degree remained virtually the same: 14 percent.

Since then, the economy has been roiled by a global pandemic and related disruptions; the chorus of college doubts has grown louder. Deitz, reflecting on his research, is still taking the long view. “I don’t think the dial has moved very much,” he recently said. “You’ve got to remember that the benefit of a degree is based on your entire life’s earnings.”

FINANCIAL AND PERSONAL REWARDS

ANNUAL EARNINGS are a more immediate measure of benefits gained from postsecondary credentials.

Generally speaking, the more you learn, the more you earn, research has shown. There are significant variations, based on degree type, occupation, gender, and race and ethnicity, according to the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. Yet, degree attainment is a primary factor influencing earning potential and career mobility. Analysis by the U.S. Department of Education shows that 25- to 34-year-olds with bachelor’s degrees had median full-time earnings of $59,600 in 2020. That was 63 percent higher than the $36,600 in median earnings for workers with high school diplomas alone. Median earnings of those with master’s degrees or higher amounted to $69,700 in 2020. Over a lifetime, people with bachelor’s degrees earn about $1 million more than people with high school diplomas alone.

But even those annual earnings might seem remote when students are considering the full costs of attending college and income they might forsake to go. Then, there are the risks of debt, which about half of college students nationwide take on to pursue their studies.

On the flip side is another set of risks – for people who do not gain postsecondary education. These include not only the loss of extra earnings, but also a missed chance to discover new ways of thinking, living, and being that may be stimulated with higher education.

Attending college can lead to better health, higher savings rates, and even increased feelings of well-being, economists Lisa Barrow, of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, and Ofer Malamud, of the University of Chicago, have written. Other researchers have confirmed benefits including increased civic involvement, such as voting, volunteerism, and philanthropy. “The value of higher education is multifaceted, not just about earnings,” according to “The Value Index,” a recently published economic report from the University of Colorado.

College is not a worthwhile investment for everyone, Barrow and Malamud wrote in a research study published in the Annual Review of Economics. Most of us have heard compelling anecdotes about college dropouts who became tech billionaires and indebted baristas and bartenders who can’t find other jobs, despite their college degrees. Even so, Barrow and Malamud found, “college is a worthwhile investment, while not necessarily for all, almost certainly for most.”

Once the full set of costs and benefits is taken into account, investing in a college education still appears to be a wise economic decision for the average person.”

— Richard Deitz and Jaison Abel, Federal Reserve Bank of New York

BENEFITS FOR SOCIETY

BEYOND BENEFITS for individuals are the benefits of postsecondary education for society.

There are some straightforward measures. For instance, nearly one in 25 Colorado workers has a degree from a CSU System campus, according to a 2021 economic impact study. Alumni income translates into more than $209 million in annual state income tax revenue and $128 million in annual sales, use, and excise tax revenue, the CSU System study showed. J. J. Ament, chief executive officer of the Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce, Colorado’s leading business advocacy group, notes in a column for STATE Spotlight that a well-educated, well-trained workforce is central to the state’s economic health.

In fact, the Morrill Act of 1862 created our national system of public land-grant universities to spark innovations and improve overall quality of life by educating the children of working-class families, with teaching originally focused in the fields of agriculture and engineering. Colorado State University is among the land-grant institutions founded to provide an excellent education for any student with the talent and motivation to earn a college degree – with benefits for graduates, their families, and society.

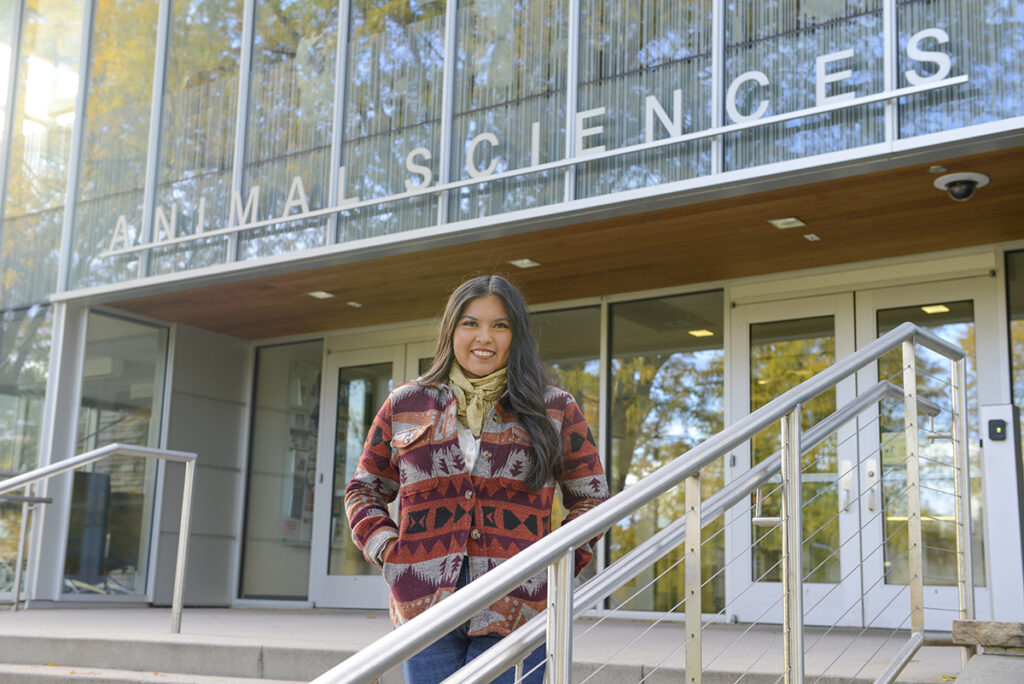

Justina Slim envisions exactly what that might mean today. Slim, 22, will graduate in Fall 2023 with a bachelor’s degree in animal science from Colorado State University. A member of the Navajo Nation, she grew up on her family’s small cattle ranch and hopes to return to beef production in her home community of Crownpoint, New Mexico, after working for a time in industry and perhaps gaining a master’s degree.

Justina Slim, a senior in animal science, has enriched her CSU classroom studies through the Seedstock Merchandising Team and work at the John E. Rouse Beef Improvement Center. Photo: Ryan Brooks.

Slim is a first-generation college student who has attended CSU – and will graduate debt-free – with the help of institutional support, federal Pell Grants, multiple scholarships, and college jobs. She gained experience during an internship at CSU’s John E. Rouse Beef Improvement Center, a large Angus cattle ranch and hay farm in southern Wyoming; through the Seedstock Merchandising Team, which teaches students to market purebred cattle; and by working as a manager at the Where Food Comes From Market, which sells meat and specialty products on campus.

“Some people think college is about the piece of paper you receive at the end,” she said. “That’s really not what it is. It’s about getting to try things out to see what you like and what you don’t, and getting to meet people with different experiences and perspectives. It’s so much more than going to class and then getting a degree.”

Ultimately, she hopes her knowledge will benefit her tribe. Slim dreams of improving and expanding Navajo cattle operations for economic development – and to ensure that fresh, nutritious, affordable food is more readily available on the reservation spanning parts of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah.

“It’s very important to me to give back to my community. I owe it to our people because I’ve been blessed to go to school. It takes a village to raise a kid, and I feel like that’s me,” Slim said.

“It’s a really big dream of mine to make a closed-loop food system so we can improve food sovereignty,” she continued, referring to food security for her tribe. She described her detailed vision for improved cattle breeding, feeding, and processing on the Navajo Nation. “I feel like we should be able to feed our people quality beef,” she said. “I can’t even begin to fathom what that would mean. It’s really important. Feeding people is really important to me.”

It’s very important to me to give back to my community. I owe it to our people because I’ve been blessed to go to school. It takes a village to raise a kid, and I feel like that’s me.”

— Justina Slim, CSU senior in animal science

UNEQUAL DEGREE ATTAINMENT

FOR ALL THE PROMISE of college, degree attainment remains both modest and highly unequal in American society. The percentage of U.S. adults with bachelor’s degrees stands at 38, up from less than 5 percent in 1940.

The GI Bill of 1944 and the Higher Education Act of 1965 helped broaden access to higher education for a more demographically diverse student population.

Yet, socioeconomic disparities remain striking. In 2020, according to estimates from the Pell Institute, 59 percent of 24-year-olds from families in the highest income quartile had completed bachelor’s degrees. That compares to 40 percent in the second quartile, 25 percent in the third, and 15 percent of young adults from the lowest-earning quartile.

Left: The Lory Student Center is a popular spot for gathering and studying on the campus of CSU in Fort Collins. Photo: Joe A. Mendoza. / Right: At CSU Pueblo, student researchers display the results of their work at an annual symposium. Photo: Jerod Young.

Top: The Lory Student Center is a popular spot for gathering and studying on the campus of CSU in Fort Collins. Photo: Joe A. Mendoza. / Bottom: At CSU Pueblo, student researchers display the results of their work at an annual symposium. Photo: Jerod Young.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 42 percent of white adults have bachelor’s degrees, and 61 percent of Asian American adults hold degrees. By comparison, 28 percent of Black adults and 21 percent of Hispanic adults have attained bachelor’s degrees.

The rural-urban divide is equally striking. The U.S. Department of Agriculture reported that 21 percent of rural adults held college degrees in 2019.

The numbers are significant, foremost, because they quantify the talent, prosperity, and lifetime opportunities that may be unlocked with more equitable access to higher education – a mission-based imperative for Colorado State and other land-grant universities. Moreover, well-managed, diverse work teams are a “recognizable source of creativity and innovation that can provide a basis for competitive advantage,” according to an article in the journal Creativity and Innovation Management.

Today’s global economy further demands cultural competence among professionals, skills that may arise when students interact with peers with diverse backgrounds, according to a study titled “Educating the workforce for the 21st century,” published in Research in Higher Education. “Given the changing demographic landscape, the role of higher education in preparing students for the challenges and complexities of a diverse society has received considerable attention,” the study said.

First-generation students make up about 25 percent of Colorado State’s total enrollment. Photo: John Eisele.

RISING COSTS AND STUDENT DEBT

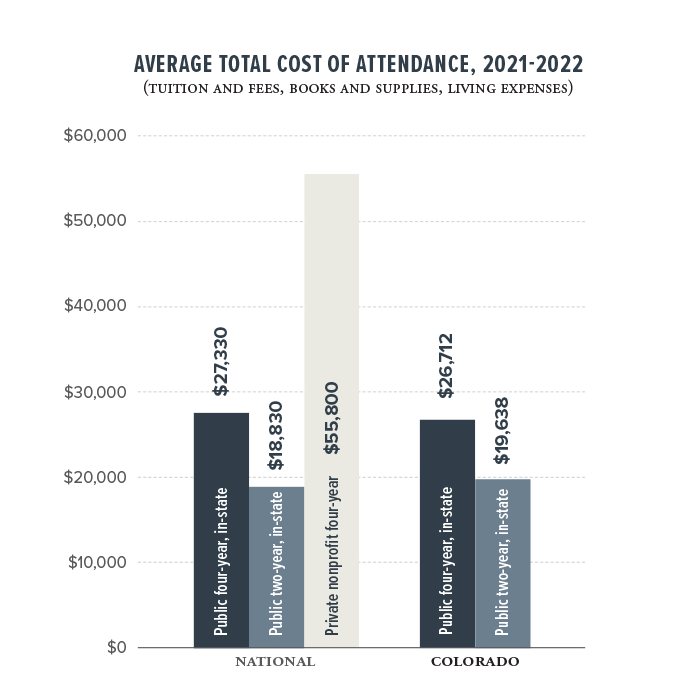

RISING COSTS of college attendance have thwarted many students; it’s one of the central concerns among those who question the value of college degrees, surveys have shown.

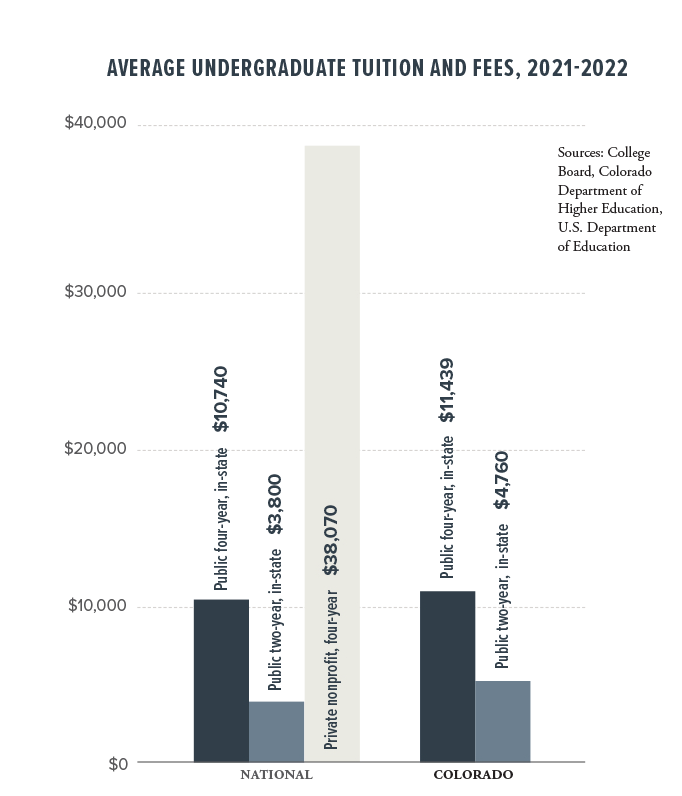

The increases are clear: At public, four-year schools nationwide, the average cost of tuition and fees in academic year 1991-1992 was $4,160, measured in 2021 dollars, according to the College Board. Thirty years later, in 2021-2022, that cost had increased to $10,740, a rise of nearly 160 percent. Until the recent surge in inflation, U.S. college prices notably outpaced inflation for many years, said Sandy Baum, a leading expert on higher education affordability with the Urban Institute in Washington, D.C.

A prime reason has been declining state investment in public higher education, a trend that has occurred across the country over time. Colorado is at the bottom of the heap: It ranked No. 49 in the nation based on public higher education appropriations per full-time equivalent student in 2021, according to a report from the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association. Only New Hampshire spent less.

The gradual defunding of public postsecondary education has had distinct results in Colorado: Responsibility for the lion’s share of tuition costs has shifted from the state to students and their families. In 2000, “the state covered 68 percent of the cost of college, while students and families were responsible for 32 percent. By fiscal year 2011-2012, the balance had effectively reversed, leaving students and families responsible for two-thirds of the costs, while the state paid a third,” the Colorado Department of Higher Education recently reported. State funding per student has lately improved in Colorado with support from the governor and Legislature. Even so, the prevailing shift in financial responsibility is one reason baby boomer and Gen X parents are often baffled by college costs.

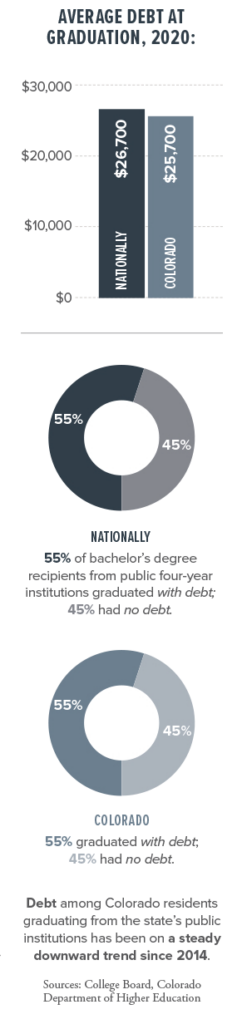

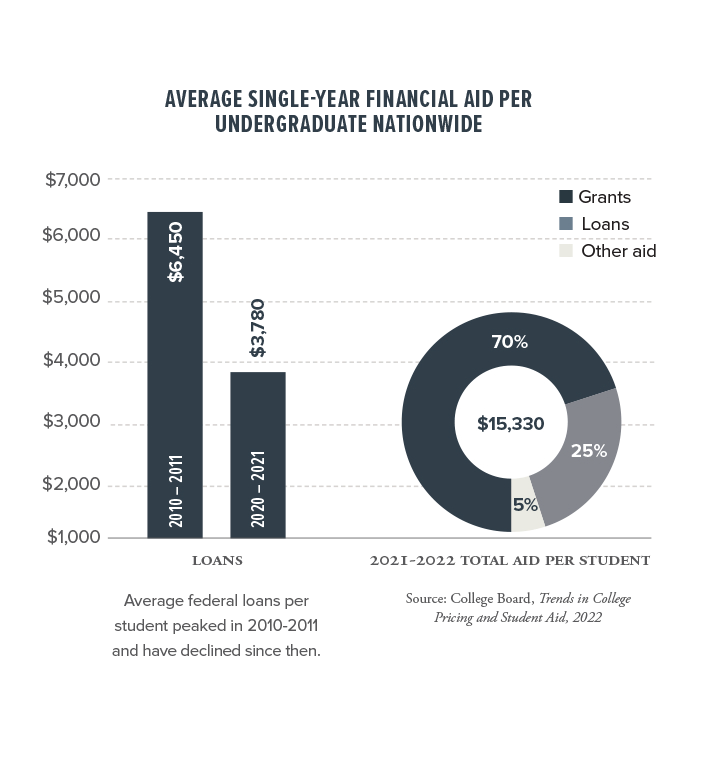

In tandem with this disinvestment, education debt has become a top worry for many college students and families. College debt is crippling for some college graduates. However, the public narrative often exaggerates the problem, Baum noted. In 2021, 7 percent of borrowers had education debt in the six figures – the scenario that most often grabs headlines. Nationwide, 55 percent of public four-year college graduates had relied on loans to pay for school in 2020; 45 percent of graduates did not have debt. Among those who borrowed, the average total was $26,700.

Debt was lower, on average, for graduates of Colorado State University, the CSU System’s flagship. Last academic year, 52 percent of CSU graduates had relied on loans to pay for school; 48 percent of graduates did not have debt. Among those who borrowed, the average total was just under $26,000. The monthly payment on such a loan might be between $200 and $300, depending on the loan term. Those with high debt relative to their income may qualify for a federal income-driven repayment plan that limits payments and may offer loan forgiveness if a balance remains after a specified period, usually 20 years.

“For most people, the difference between your earnings over the next 20 years and what they would have been without a college degree is going to be far more than enough to repay your loans,” Baum said.

A human anatomy class convenes in a state-of-the-art laboratory at Colorado State University. Photo: Mary Neiberg.

THE ROLE OF FINANCIAL AID

A PLETHORA OF AID is available to help college students avoid debt. These options are critical at land-grant universities, in particular, because affordability is central to access – an institutional imperative. In fact, CSU students from the lowest-income households may attend the university at virtually no cost if they take advantage of support available. Data show that most students nationwide receive some type of aid to attend college, whether federal, state, institutional, donor funded, or, very often, a mix. For this reason, posted college sticker prices typically do not reflect the final amounts paid.

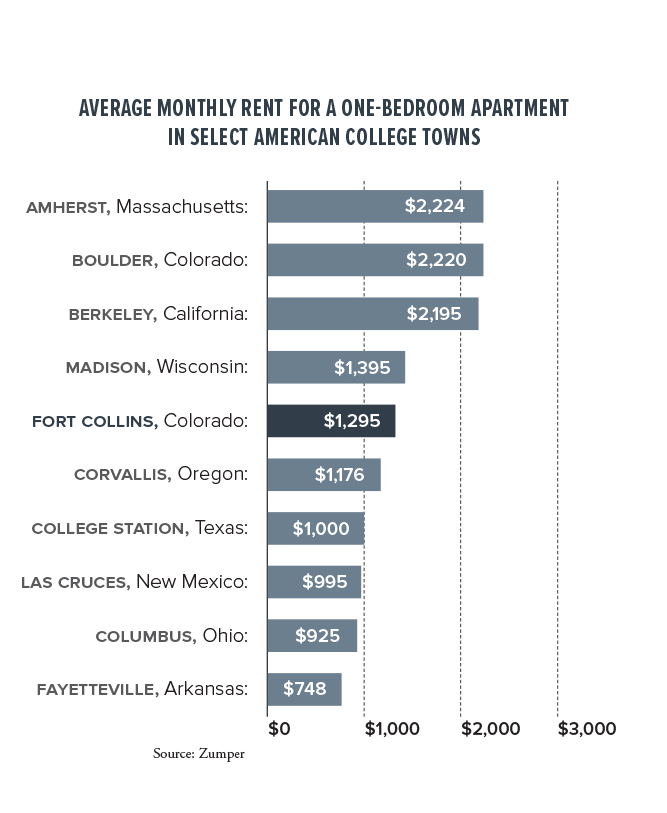

Among the best-known resources are federal student loans and federal Pell Grants. The grants don’t have to be repaid and are a main way students with limited resources pay for college. Importantly, Pell Grants provide funds for living expenses, which may easily double the cost of tuition and fees, particularly in college towns with relatively high rental rates. Yet, even with the annual Pell maximum increasing by $400 last year to $6,895, the grant doesn’t have the purchasing power it once had, given rising tuition costs and a high price tag for living in many college towns.

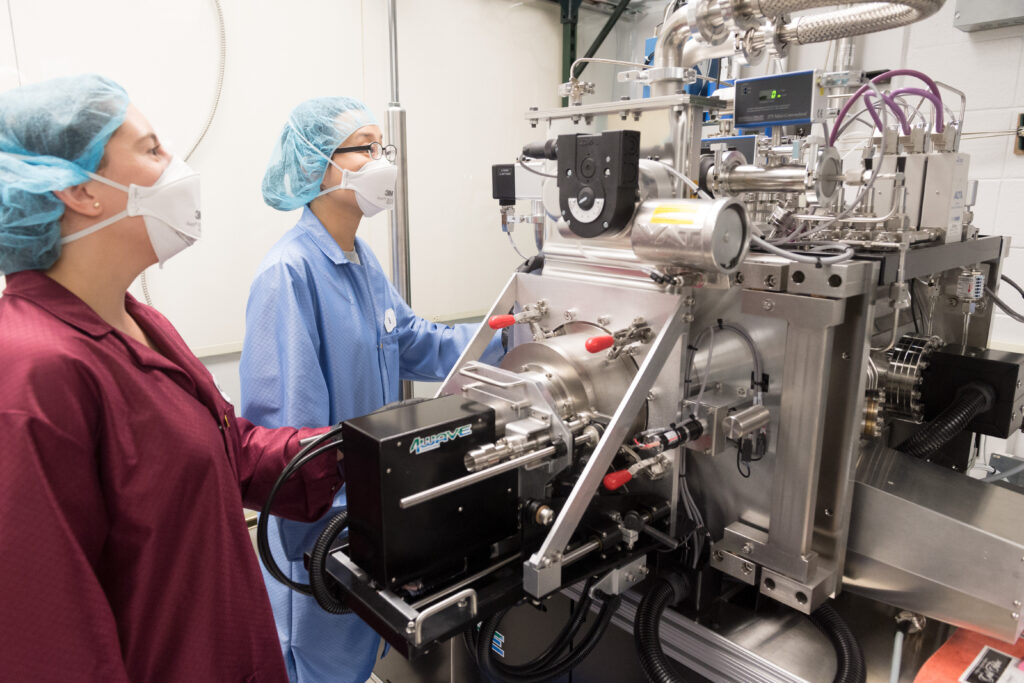

Left: Undergraduates examine brain structures during a neuroanatomy lab at Colorado State. Photo: Mary Neiberg. / Right: A postdoctoral fellow and student conduct research at CSU’s Laboratory for Advanced Lasers and Extreme Photonics. Photo: William A. Cotton.

Top: Undergraduates examine brain structures during a neuroanatomy lab at Colorado State. Photo: Mary Neiberg. / Bottom: A postdoctoral fellow and student conduct research at CSU’s Laboratory for Advanced Lasers and Extreme Photonics. Photo: William A. Cotton.

Institutional support – provided by colleges and universities – is increasingly important for many students. CSU has a landmark program called the Colorado Tuition Assistance Grant that aids in-state students from low- and middle-income families. It started in 2011 in response to the Great Recession. Since then, the program, known as CTAG, has disbursed more than $210 million to more than 33,000 students. Thousands gain assistance each year. The program has helped to refocus work of the university’s Division of Enrollment and Access. Now, a central question is, “How much does a student at CSU need to be successful?” said Tom Biedscheid, assistant vice president for the division.

CSU Pueblo has a similar scholarship program, called Colorado Promise. The new program offers free tuition to eligible Colorado students from low-income households.

Colorado’s land-grant university, flagship of the CSU System, top-tier research institution

- Total enrollment, Fall 2022: 27,956

- 25% diverse; 24% first generation

- Average tuition cost, academic year: $9,709

- 52% of students borrow; among those, average debt at graduation is $25,998

- Students who receive financial aid: 60%

- FAFSA completion rate: 67%

- Median starting salary for graduates: $53,290

Regional university; designated as a Hispanic- serving institution, making it eligible for student- focused federal grants

- Total enrollment, Fall 2022: 3,551

- 51% diverse; 44% first generation

- Average tuition cost, academic year: $6,539

- 43% borrow; among those, average debt at graduation is $21,923

- Students who receive financial aid: 73%

- FAFSA completion rate: 89%

- Median starting salary for graduates: $44,449

The nation’s first fully online nonprofit university with accredited degree programs; designed for working adults who wish to upskill or reskill

- Total active students, Fall 2022: 13,580

- 30% diverse; 30% first generation

- Average tuition cost, annually: $8,400

- 40% borrow; among those, average debt at graduation is $30,929

- Students who receive financial aid: 32%

- FAFSA completion rate: 46%

- CSU Global students are typically working while in school, so starting salary is less relevant than it is for other campuses. An independent ROI study found that graduates realize a return of $4.90 in higher future earnings and benefits for every dollar invested in their CSU Global educations.

HOW TO PAY: A CASE STUDY

CODY GAMET, 37, is among the students who were surprised to discover the range of support available. In 2010, he was working hourly wage jobs and struggling with drug addiction. Then, his mother died of ovarian cancer – a loss that pushed Gamet to think deeply about his life and how he wanted to live it. “I thought, ‘My mom’s in heaven looking down at me, and I don’t want her to see this.’ I want something more,” Gamet, of Greeley, Colorado, remembered.

He got clean and asked coworkers, some of whom were college students, how he might pay to attend Aims Community College. Gamet had grown up thinking college was unaffordable, but he soon learned about the range of scholarships and federal aid available for students.

By 2018, with help from multiple scholarships and Pell Grants, Gamet had earned two associate degrees from Aims – in computer information systems and liberal arts. He was the first in his family to earn college credentials. Along the way, he discovered a passion for leadership and helping others; he served as president of the Aims student body, worked as a peer educator, earned top student honors, and was a featured commencement speaker. He graduated with 4.0 grade point averages.

Now, Gamet is pursuing a bachelor’s degree in organizational leadership from CSU Global. He has two university scholarships and a Pell Grant; that aid, and part-time work as a cook, will allow Gamet to graduate this spring without debt, he said.

“I have a solid financial support system,” Gamet said. “If you think you can’t afford college, get some more information and talk to someone. There’s so much support available. Once you start asking for support, you’ll gain support. And as you gain support, you’ll gain a network of support, and you’ll look back and think, ‘How did I ever think this was a barrier?’”

He can see himself working in leadership positions in a variety of industries. “As I’ve gone through college, I’ve gained so much confidence and knowledge, and I have a sense of accomplishment knowing I’m a better person,” Gamet said. “The value of that development is immeasurable.”

Cody Gamet, a CSU Global student, secured the financial aid he needed to pursue associate and bachelor’s degrees. Photo: Ryan Brooks.

FAFSA AND ADVISING

A NECESSARY first step is completion of the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, or FAFSA. Yet, despite its role as a doorway to student aid and college, a surprising number of students fail to complete the application.

A report for the Colorado Department of Higher Education found that, in the 2020-2021 application cycle, 46 percent of Colorado seniors completed the form. The national average was 52 percent. The report estimated that Colorado students miss out on $30 million in grant aid each year as a result.

In 2000, the state of Colorado covered 68 percent of the cost of college, while students and families were responsible for 32 percent. By fiscal year 2011-2012, the balance had effectively reversed.”

— Colorado Department of Higher Education

For this reason, CSU Pueblo has started new school partnerships to help students and families navigate the college admissions process, including FAFSA completion. The CSU System’s new rural outreach initiative is another effort aimed, in part, at improving access to learning in rural parts of the state; much of this outreach is led by CSU’s Office of Engagement and Extension.

Advising and flexibility in degree attainment have proved critical to success for many students. A national organization called College Track, based in Oakland, California, provides a model for guiding first-generation students from low-income communities to degree completion and beyond; its work is aimed at unlocking doors to economic mobility and lifelong wellness. College Track runs a dozen centers that support thousands of students from the beginning of high school through college and the start of their careers. It works in Aurora and Denver, among other locations. A new partnership with the CSU System will establish a College Track center at CSU Spur in north Denver; among those supported will be students pursuing degrees at System campuses.

“There are talented students in all walks of life and in every high school in America,” said Shirley Collado, College Track president and CEO. “They just need to be seen and to have the opportunity.”

Left: Moby Arena is the site of a pep rally during Ram Welcome, an orientation tradition at Colorado State University. Photo: John Eisele. / Right: Students graduating from the College of Natural Sciences gather in Moby Arena again – this time, for commencement. Photo: Joe A. Mendoza.

Top: Moby Arena is the site of a pep rally during Ram Welcome, an orientation tradition at Colorado State University. Photo: John Eisele. / Bottom: Students graduating from the College of Natural Sciences gather in Moby Arena again – this time, for commencement. Photo: Joe A. Mendoza.

THE IMPORTANCE OF RETENTION

OF COURSE, students must attain their degrees to fully realize the opportunities tied to higher education and to better position themselves to pay off debt. To improve retention – and to broaden student learning – schools emphasize student services and co-curricular activities that support and enrich the college experience.

Among other benefits, student involvement on campus improves academic performance, cognitive development, well-being, and leadership, according to the Center for the Study of Student Life at the Ohio State University. Such involvement may take a number of forms, from community service to membership in clubs and organizations.

Phillip Flores, 23, demonstrates the benefits of campus involvement. Flores will graduate from CSU Pueblo this spring with a master’s degree in mechatronic engineering and bachelor’s degrees in both engineering and Spanish. He is a first-generation Chicano student from Pueblo whose college experience started even before he stepped on campus, with the CSU Pueblo President’s Leadership Program. The academic leadership program gave Flores the chance to travel and to work closely with corporate and community leaders. It inspired him to branch out further: He became vice president of CSU Pueblo student government and was named 2022 Student Leader of the Year by the Denver Metro Chamber Leadership Foundation and the Boettcher Foundation.

“It’s been huge to my foundational development because now I want to be a leader,” Flores said of his campus experiences. “The connection is probably the biggest thing – having a group of people I knew before coming into college was huge. I was able to meet friends who are intentional about what they are doing. We’re all going towards completing our dreams.”

Photo at top: An economics class brings students to an auditorium on the campus of CSU in Fort Collins. / Photo: Joe A. Mendoza

SHARE