AMACHE

How a teacher, his students, and a community of Japanese Americans helped resurrect history in southeastern Colorado

By Coleman Cornelius | Feb. 13, 2023

Photography by Tanya Fabian | Historical imagery courtesy of the National Archives

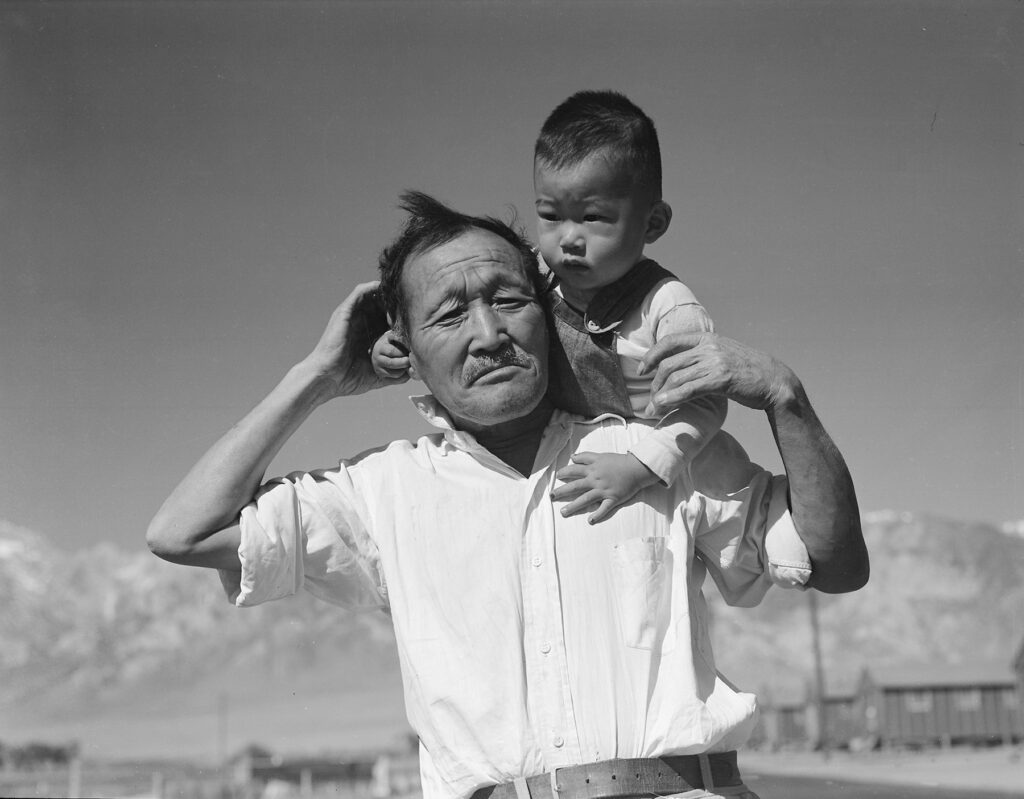

THERE WERE MILITARY police posted in eight guard towers around the fenced compound. They aimed machine guns and flashed searchlights at an estimated 7,300 incarcerated Japanese Americans, who existed – always under watch – at school, in farm fields, and in barracks on the barren prairie.

It’s an image fixed in the memory of Jim Yoshihara. He was only 3 years old at the start of his confinement, but the relentless threat of gunfire has stayed with him for eight decades.

“My most vivid memory is of soldiers in gun towers. I heard they were there to protect us, but the guns were always pointed in,” Yoshihara remembered, sitting in the living room of his home in Lafayette, Colorado. “It was more like a concentration camp than anything. They called it an evacuation center, as if they were protecting us. But that was to soften the blow.

“It’s a tragic thing that happened,” he added quietly.

Jim Yoshihara of Lafayette, Colorado, is a CSU alumnus who was incarcerated with his family at Amache.

Yoshihara, now 83, was born in Venice, California, on the outskirts of Los Angeles, where his family grew strawberries and vegetables on a small truck farm. His father, Yasutaro, had emigrated from Japan and was a naturalized American citizen; his mother, Kumiko, was born in Los Angeles, also a U.S. citizen.

Their lives were upended in February 1942. It was two months after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, on Dec. 7, 1941, prompting the United States to declare war on Japan and to enter World War II. Amid raging anti-Japanese racism and fears of national security breaches, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, resulting in forced removal of an estimated 110,000 people of Japanese descent from immigrant enclaves on the West Coast.

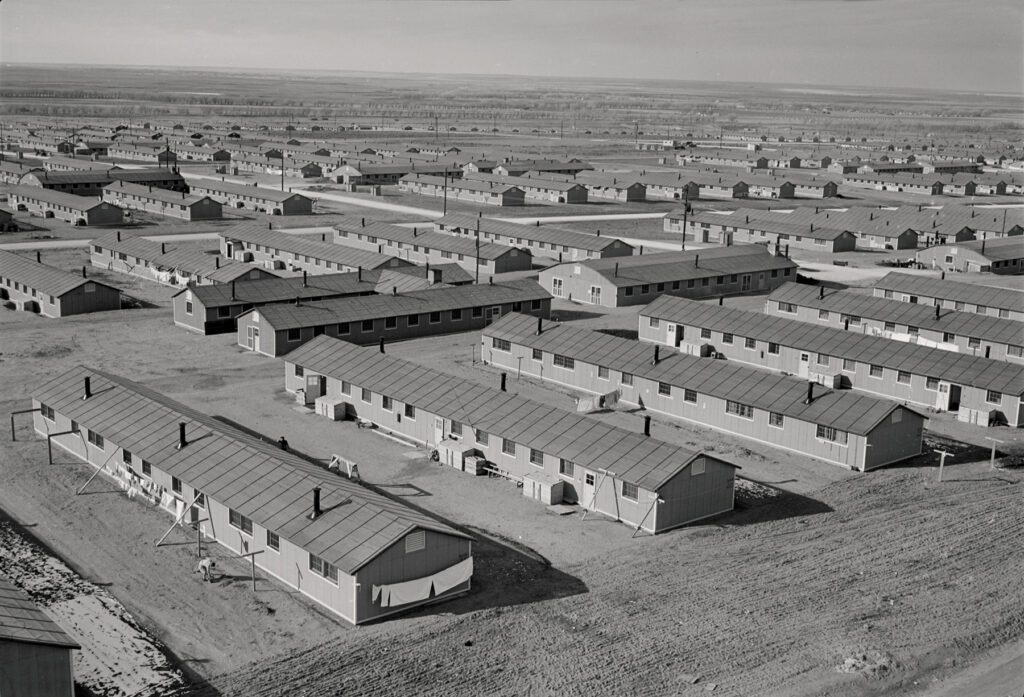

At Amache, row upon row of barracks held about 7,300 Japanese Americans uprooted from California. Amache is on the outskirts of Granada, in southeastern Colorado, and was one of 10 Japanese American internment camps in the mainland U.S. during World War II.

Those uprooted would be hauled to temporary detention centers at livestock pavilions and racetracks, then on to hastily constructed prison camps. From 1942 to 1945, a total of 120,000 people ultimately were confined in 10 inland camps, most in remote reaches of Western states. The majority of those incarcerated were American citizens. They had committed no crimes, yet all lost personal liberties; most lost homes, businesses, and other property as well, according to the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

Like others, the Yoshiharas – three adults and three little children – were allowed one suitcase per person when they left home. The family was transported to an “assembly center” at Santa Anita Park, a racetrack in north Los Angeles. There, they were relegated to a horse stall for several weeks; other families packed into adjacent stalls. The Yoshiharas slept on straw atop dirt soaked with horse urine and manure. Many incarcerees remembered the overcrowding and the oppressive stench.

RECALLING PAINFUL HISTORY

“My family was ordered by the Army to leave our home and 20- acre fruit and vegetable farm in Yuba City, California. The timeframe given us was less than one week. We were told to report to the local train depot with only what we could carry. No destination given. No reason given, except two vague words, ‘military necessity.’ No charges were leveled against us. No trial. No hearings. We were loyal, patriotic, law-abiding citizens who had never done anything wrong. Why were we treated this way? Why were we singled out for eviction and incarceration? … While we were in Amache, we lost everything that we owned in California. We lost our home, our farm, our equipment, everything. Over time, our sense of family, of purpose, and future was destroyed. … This history should not be ignored, forgotten, or remain invisible.”

– Bob Fuchigami, 91, of Evergreen, Colorado, while testifying before a congressional committee in Spring 2021 to advocate for Amache’s designation as a National Historic Site

Then, not knowing their destination, the family rode by train to the euphemistically named Granada Relocation Center in southeastern Colorado, about 140 miles east of Pueblo, near the Kansas border. For three years, they were confined at the isolated prison camp, better known as Camp Amache. It was named for Amache Ochinee Prowers, a Southern Cheyenne woman who, with her husband, once ran a cattle ranch and mercantile not far from Granada.

Yoshihara, known by his given name, Akio, meaning “bright and clear,” was assigned the identification number 18289F. He lived in a 16-by-20-foot room with his sister, brother, mother, father, and paternal grandfather. Yoshihara recalled the panic he felt getting lost in row upon row of barracks. His father became a cook in a mess hall, allowing him the rare chance to drive a truck out of the prison camp for supplies. Their housing, with no insulation, provided little protection from the elements.

“It was desolate. In the summer, it was hotter than hell, and in the winter it was bitter cold,” Yoshihara said. “We had a brick floor, a potbelly stove, army cots with one blanket each, no running water, and one lightbulb in the center of the ceiling. I remember we had a community bathhouse and outdoor toilets, and it was really bad because no one had any privacy.”

Clockwise from top left: Kiana Herrera, left, and Vanessa Ayala, right, are among the current Granada School students studying Amache as part of their high school course work and working at Amache Museum to share historical information with visitors; Brandon Gonzales, a current student at Granada School, has worked at the Amache Museum and tended the cemetery at the historic site; Tanner Grasmick was introduced to Amache as a high school student, attended CSU Pueblo, then returned to Granada as a history teacher – who is now preparing to take over leadership of the school’s Amache project; Jaime, left, and Antonio Huerta are brothers from Granada who traveled to Japan with the Amache project and later attended CSU Pueblo (Photo: Mary Neiberg); Trinidie Quintana, a senior at Granada School, discusses the prison camp while working at Amache Museum.

From top: Kiana Herrera, left, and Vanessa Ayala, right, are among the current Granada School students studying Amache as part of their high school course work and working at Amache Museum to share historical information with visitors; Trinidie Quintana, a senior at Granada School, discusses the prison camp while working at Amache Museum; Brandon Gonzales, a current student at Granada School, has worked at the Amache Museum and tended the cemetery at the historic site; Tanner Grasmick was introduced to Amache as a high school student, attended CSU Pueblo, then returned to Granada as a history teacher – who is now preparing to take over leadership of the school’s Amache project; Jaime, left, and Antonio Huerta are brothers from Granada who traveled to Japan with the Amache project and later attended CSU Pueblo (Photo: Mary Neiberg).

Last summer, Yoshihara returned to Amache to reflect on a time and place that powerfully influenced his life and the lives of many other Japanese Americans. He does not feel bitter about his family’s imprisonment, Yoshihara said. Rather, he adopted the Japanese philosophy of shikata ga nai, roughly translated to “it can’t be helped” – a sense that he and others must move forward with dignity.

Yoshihara built a life after Amache, though many years were blighted by bigotry and racism, he remembered. His family settled in Lafayette, where they returned to farming and eventually opened a greenhouse and floral shop, Lafayette Florist, which is now run by Yoshihara’s nieces. At the start of first grade, Yoshihara adopted the name Jim in an effort to assimilate. It didn’t stop years of slurs, bullying, and schoolyard fights.

Later, he served in the U.S. Army, as did many former camp incarcerees who wanted to demonstrate their allegiance as citizens of the United States, to prove their commitment to the nation. In 1966, Yoshihara earned a bachelor’s degree in art from Colorado State University, while his late wife, Maryann, worked as a nurse to support them. The couple raised two daughters and for 30 years ran their own floral shop, Artists Three Ltd., near downtown Boulder.

Granada School students learn about Amache as part of a history class. Many have been touched by stories of Amache incarcerees who volunteered to serve in the U.S. military during World War II; soldiers’ names are listed on the Amache Honor Roll.

NOW, YOSHIHARA VIEWS the prison camps as a grave historical injustice – a wrong that cannot be righted but should be remembered for shocking civil rights violations. He often has been jarred by ignorance of the camps.

“Hardly anybody knows about it. It was never really taught in school,” Yoshihara said. “It’s strange to me because I lived that, so it’s like you didn’t really exist. It validates ‘You didn’t exist’ when even adults don’t know about it. People should learn from society’s mistakes so it doesn’t happen again.”

Left: Jim Yoshihara, left, and his sister, Ann, returned to Amache nearly eight decades after their family was held there. John Hopper, right, a CSU alumnus and educator at Granada School, has worked to preserve Amache history. Right: The Amache Museum contains relics of life at the prison camp.

Top: Jim Yoshihara, left, and his sister, Ann, returned to Amache nearly eight decades after their family was held there. John Hopper, right, a CSU alumnus and educator at Granada School, has worked to preserve Amache history. Bottom: The Amache Museum contains relics of life at the prison camp.

Recently, the wrongs he described have gained heightened public attention. Last year, President Joe Biden signed a bill designating the former prison camp on the edge of Granada as a National Historic Site. As a result, the site is officially recognized for its historic significance and will be owned and managed by the U.S. National Park Service, gaining permanent protection and support to help tell the history of Japanese American incarceration during World War II. With Amache’s designation, three of 10 former mainland prison camps are deemed National Historic Sites. Members of Colorado’s congressional delegation introduced legislation to elevate Amache in the National Park System: U.S. Sens. John Hickenlooper and Michael Bennet and U.S. Reps. Joe Neguse and Ken Buck.

“As a nation, we must face the wrongs of our past in order to build a more just and equitable future,” Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland said of the designation. She visited the site last year on the 80th Day of Remembrance, commemorating the anniversary of the executive order that triggered Japanese American imprisonment.

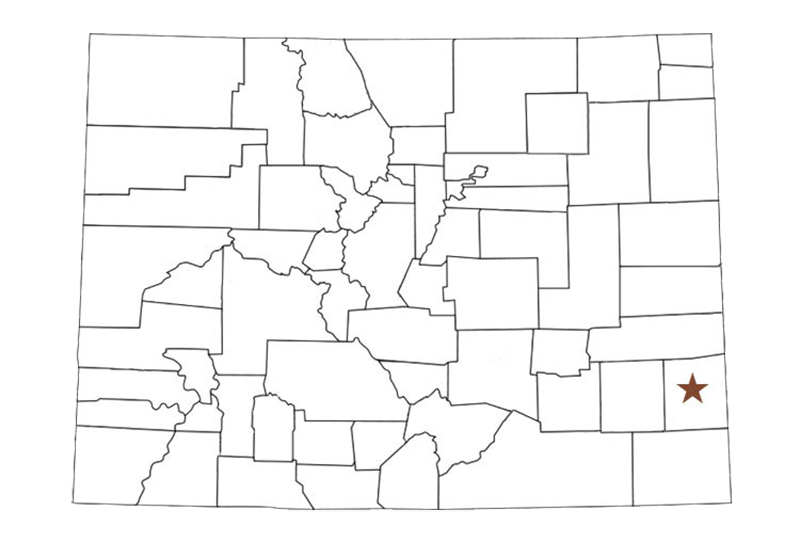

JAPANESE AMERICAN PRISON CAMPS

Ten remote prison camps, called relocation centers, were run on the U.S. mainland by the War Relocation Authority and were used to incarcerate an estimated 120,000 people of Japanese descent during World War II. The camps operated from 1942 to 1945 at the sites below. The Granada Relocation Center in Colorado, better known as Camp Amache, was the smallest. It held 7,300 people at a given time; 10,000 were there over the course of three years. The Honouliuli Internment Camp, a National Historic Site, was the largest of several confinement sites in Hawaii.

—GILA RIVER and POSTON** in Arizona

—GRANADA* in Colorado

—HEART MOUNTAIN** in Wyoming

—JEROME and ROWHER** in Arkansas

—MANZANAR* and TULE LAKE*** in California

—MINIDOKA* in Idaho

—TOPAZ** in Utah

*National Historic Site, **National Historic Landmark, ***National Monument

Source: U.S. National Park Service

THE DESIGNATION TOOK years of advocacy, and alumni of Colorado State University and CSU Pueblo are among those who have taken a lead in public education, fundraising, and site preservation, resulting in Amache’s standing as a National Historic Site.

“It’s huge,” Traegon Marquez, a Granada town councilor, said of the designation. After growing up in Granada, Marquez earned a prestigious Daniels Scholarship and began his college studies at CSU Pueblo in 2011. He later returned to his hometown, where he works as a financial adviser and high school athletics coach. Marquez is among the officials who have worked to transfer 480 acres of Amache property from town of Granada ownership to the National Park Service.

“The unfair treatment of Japanese Americans stuck with me growing up. It’s history we need to remember,” said Marquez, who has helped with Amache reconstruction. “It also shows that, even with tough parts of our history, there are great stories of resilience to come out of it. I hope a lot more people get to see Amache.”

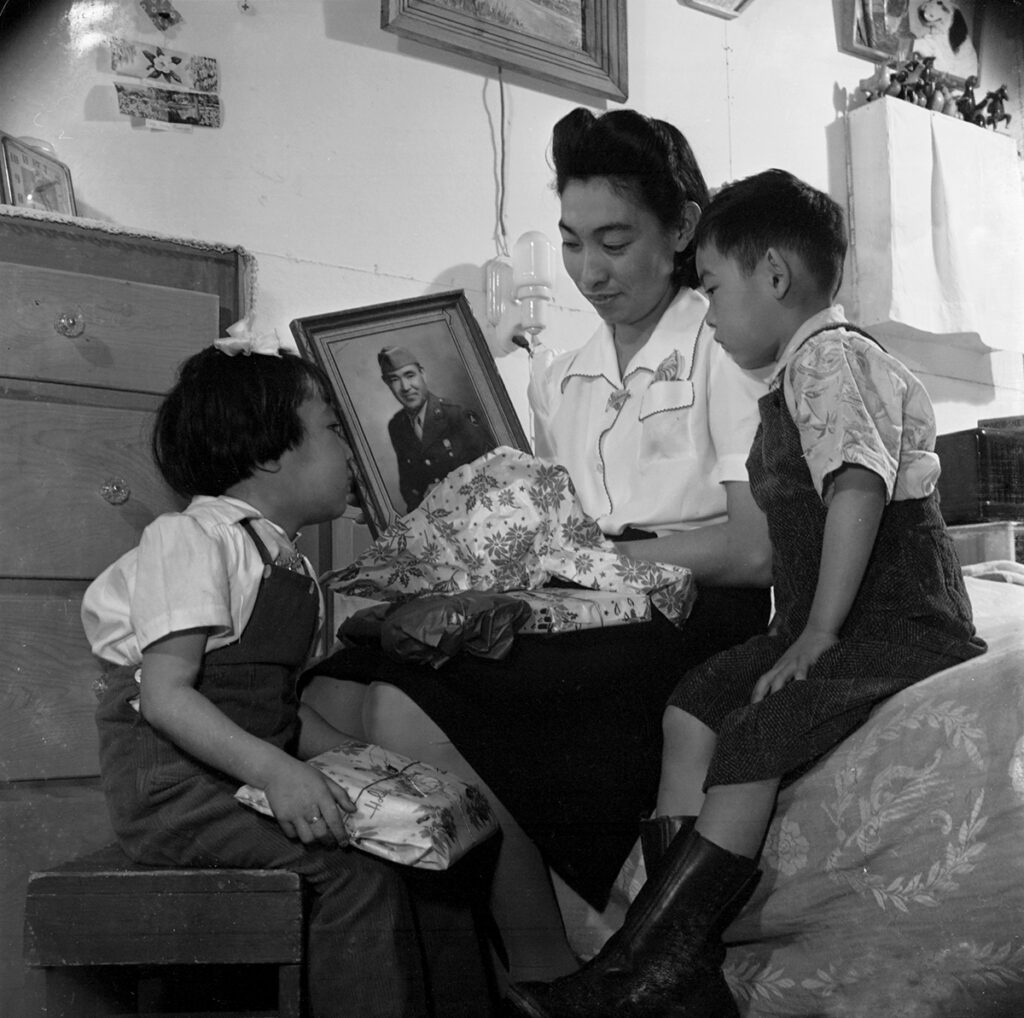

Left: Young men are driven from the Granada train station to Camp Amache in 1942. Top right: Incarcerees lived in spartan and often difficult conditions at Amache. Bottom right: A propaganda photograph, from the U.S. War Relocation Authority, is intended to depict a happy Japanese American family at Amache at Christmastime, when they open the gift of a photograph of their soldier husband and father. The U.S. War Relocation Authority commissioned numerous photographs of life in Japanese American internment camps; many conferred a false impression of normalcy and even ease.

Top: Young men are driven from the Granada train station to Camp Amache in 1942. Middle: Incarcerees lived in spartan and often difficult conditions at Amache. Bottom: A propaganda photograph, from the U.S. War Relocation Authority, is intended to depict a happy Japanese American family at Amache at Christmastime, when they open the gift of a photograph of their soldier husband and father. The U.S. War Relocation Authority commissioned numerous photographs of life in Japanese American internment camps; many conferred a false impression of normalcy and even ease.

The National Historic Site is expected to bring between five and 12 new jobs and perhaps 25,000 annual visitors to Granada – a big boost for an Eastern Plains town with a population of 431 people, he noted. Already, about 1,000 people visit each month.

A driving force behind Camp Amache’s increased visibility is John Hopper, a high school teacher and dean of students at Granada School, a K-12 school where this year’s senior class numbers just 16 students. For 30 years, Hopper has worked to spread the lessons of Amache – often volunteering up to 20 hours per week.

“Amache shows us the dangers of prejudice and discrimination; that’s the important thing about it,” Hopper recently said, while gathered with a handful of his current and former students at the Amache Museum in downtown Granada. “We need to remember the U.S. motto, ‘E pluribus unum’ – out of many, one. We’re all American citizens, and the Constitution protects us all. We all have civil liberties. If we don’t remember that, this can happen again.”

A reconstructed recreation center hints at life in a barren setting.

HOPPER HAS BEEN honored by the Consulate General of Japan in Denver, the American Historical Association, and History Colorado for his commitment to classroom and public education about Camp Amache. But his greatest honor, Hopper said, is inspiring high school students to discover history that has been largely hidden in their own backyard – often, directly from the people who lived it.

“My motivation for teaching is Mr. Hopper. I’ve admired him forever,” said Tanner Grasmick, 27, who learned about Camp Amache in Hopper’s classroom. After graduating from high school in Granada, Grasmick earned a bachelor’s degree in history at CSU Pueblo and in 2018 returned to teach alongside his mentor. He will take over Amache teaching at Granada School after Hopper’s retirement. “The school and this community gave me a lot growing up,” Grasmick said, “and I want to give back.”

Amache incarcerees harvest spinach from a compound field.

Hopper was raised in Las Animas, about 50 miles west of Granada. He attended Colorado State University in Fort Collins and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in history in 1988. He then earned a master’s degree in secondary education from Adams State College in Alamosa. Even while pursuing his graduate degree, Hopper started teaching at Granada School, where he has been ever since.

Early in his career, in 1993, Hopper determined he needed a challenging project for his motivated high school students. “We’ve got to help these students excel,” he realized. That’s when he thought of Emory Namura, a gregarious family friend who was 73 years old and had worked for years as an X-ray technician and administrator at Bent County Healthcare Center in Las Animas. In his early 20s, Namura had been confined at Amache. He might be willing to share his story with students, Hopper thought. An oral history project with Namura would fill in missing details about local history, the teacher realized. It could bring to light information about people who had lived at the windblown site that held little more than sagebrush and some inconspicuous building foundations. Structures had been removed or demolished after the camp closed in 1945.

“I didn’t think it would grow into what it is today,” Hopper said of the school project.

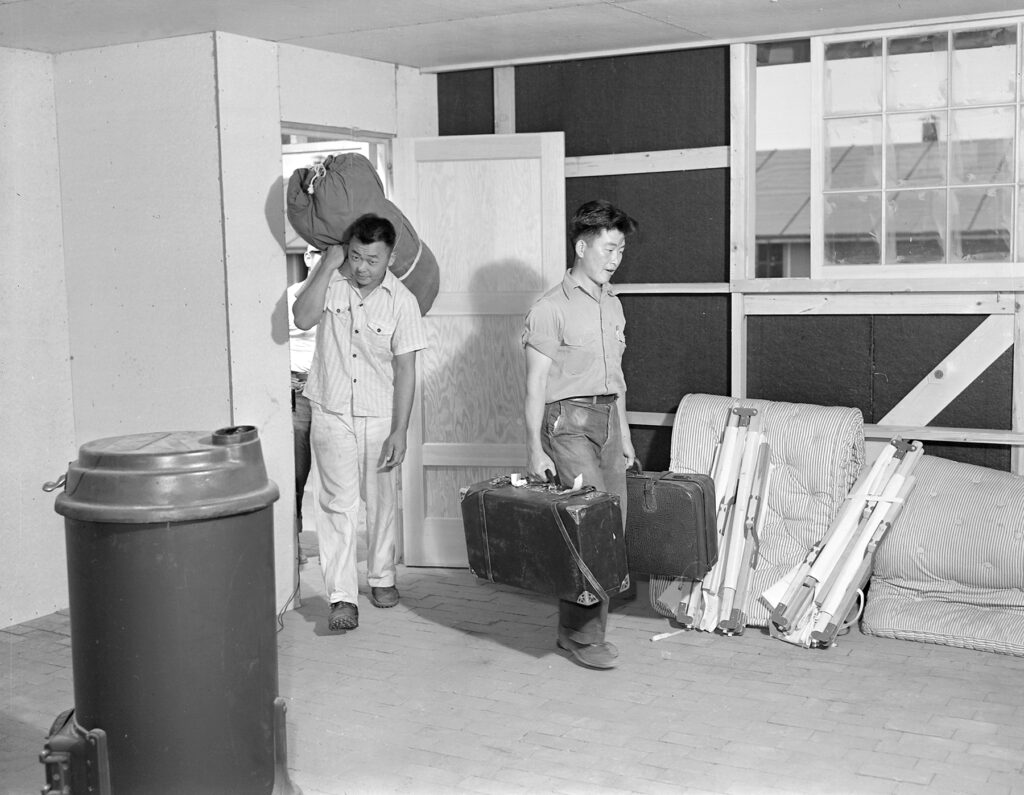

Left: Money spent to construct schools at Amache sparked protest from outside community members. Right: People relocated to Amache and other prison camps could take only what they could carry from their homes.

Top: Money spent to construct schools at Amache sparked protest from outside community members. Bottom: People relocated to Amache and other prison camps could take only what they could carry from their homes.

Namura readily agreed to be interviewed. Granada high schoolers learned his family had owned a home and a thriving dry cleaning business in California. Namura had built his skills as an X-ray technician working at the prison camp’s hospital. That’s where both his parents died, Namura told the students. He met his wife, Tayeko, at the camp, and the couple eventually settled in Las Animas, having nothing left of their earlier lives.

“He was a wealth of information. He wanted to teach the younger generation about what happened,” Hopper said of Namura, who died in 2004. “When we found out about his story, it was like, ‘Oh, dang, man.’ Imagine your parents have a nice business and a nice home, then they lose everything they worked for because of unjust imprisonment and die at Amache. That’s heart-wrenching.”

John Hopper, a Colorado State University alumnus, founded the Amache Preservation Society and is dedicated to teaching Granada School students about the important history in their own backyard. The society will continue its work, even with the new National Historic Site designation.

Such stories have had a profound impact on students through the years. “Japanese Americans were removed from their homes by the U.S. government, and when the war was over they often had nothing to go back to,” said Vanessa Ayala, a Granada senior who worked last summer at the Amache Museum.

“They had to start from scratch,” Grasmick added. “That’s devastating.”

The interaction with Namura led to a second discussion, which led to a school visit by three former internees from around the country. They sat in the library telling students about life in the camp. By 1998, five years into the school project, Hopper and his students had unearthed dozens of stories, and their work helped build connections among former incarcerees and their relatives; 12 large buses arrived that year carrying people for a reunion. Since then, annual pilgrimages, held each May, have attracted as many as 250 people. Close partnerships with Japanese American organizations, including the Denver Central Optimist Club and Nikkeijin Kai of Colorado, have sparked renewed interest in Amache and have provided essential support for student learning and Amache site preservation.

Archival imagery, taken by the U.S. War Relocation Authority, was meant to show pleasant aspects of life at Amache, including a watercolorist at work and baseball games in the camp.

THE SCHOOL PROJECT grew in other ways. Since 2007, about three dozen Granada students have traveled through a cultural exchange program from their rural Colorado town to cities all over Japan. They have stayed with host families and have presented information about Amache to Japanese audiences.

“What we were able to offer was a story of resilience. Amache showed us we have a duty to represent those who don’t have a voice or who aren’t able to represent themselves. It was an opportunity to give a voice to maybe something that hasn’t had a voice in a long time. The things Japanese Americans went through should not be swept under the rug,” said Antonio Huerta, 27, who visited Oita, Japan, in 2015. After attending Granada School, Huerta went to CSU Pueblo, where he was student body president and earned a bachelor’s degree in business and an M.B.A.

Left: The foundations of barracks and other buildings mark the former compound site; lumber and other materials were removed and reused elsewhere after the camp closed. Right: The Amache cemetery is a meaningful spot for many visitors.

Top: The foundations of barracks and other buildings mark the former compound site; lumber and other materials were removed and reused elsewhere after the camp closed. Bottom: The Amache cemetery is a meaningful spot for many visitors.

Now, Huerta is Southern Colorado regional director for the office of U.S. Sen. John Hickenlooper. He had a front-row view of the legislative process that led to Camp Amache’s designation as a National Historic Site. It was especially satisfying after his school experience, Huerta said. “Japanese American incarceration was a dark part of U.S. history and a dark part of world history, but a part you don’t normally talk about,” he said. “That’s exactly why Amache should be a National Historic Site.”

Their time in Japan – combined with presentations in Colorado – has provided Granada students with an expanded sense of the world, humanity, and community service. The experiences have helped students build the confidence and communication skills needed for later studies and careers, Jaime Huerta, 24, said. Jaime traveled to Japan with his older brother, Antonio; like his brother, Jaime was a student leader at CSU Pueblo and graduated last year with bachelor’s and master’s degrees in athletics training.

“Having that opportunity to go out and make a small change by showing people true stories from Amache felt like we had a bigger purpose,” Jaime said.

All the Japanese American prison camps were located in remote sites, most in the West.

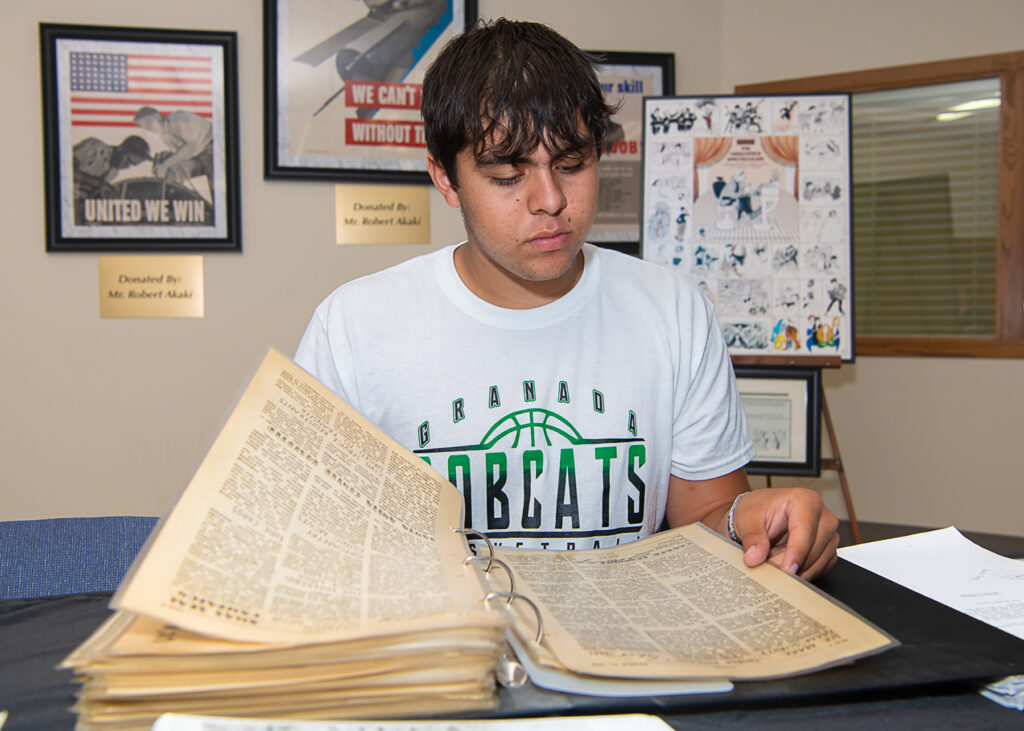

THROUGH THE YEARS, the Camp Amache study project evolved into a yearlong history elective, now a permanent part of the Granada School curriculum. Meantime, Hopper founded the Amache Preservation Society, a nonprofit dedicated to camp preservation and public education. With the help of students and volunteers, the organization runs the Amache Museum in downtown Granada; it houses a library and a wealth of artifacts. To fund this work, the Amache Preservation Society raises about $100,000 each year in grants and donations. The organization will continue its work, even after the National Park Service assumes management of Amache.

At the Amache Museum, visitors find many signs of camp life; among them, suitcases used by internees, origami objects made with Marlboro cigarette wrappers, wood carvings, and the national instrument of Japan, a koto. Visitors learn that those detained worked in farm fields, published a newspaper, played sports, and worked in a silkscreen shop producing promotional posters for the U.S. Navy. Original documents and letters offer insights into life behind barbed wire.

Left: Nancy Oki was the last baby born at Amache during its three-year operation. Right: Former incarcerees crowd the Granada railway platform as they depart Amache.

Top: Nancy Oki was the last baby born at Amache during its three-year operation. Bottom: Former incarcerees crowd the Granada railway platform as they depart Amache.

On display, for instance, is Marion Konishi’s typewritten valedictory, which she delivered for fellow Amache school graduates and their families in June 1943. In the upper right-hand corner, Konishi typed her name, the date, and her family’s barracks number, 6E-12-D. The address reads, in part:

One and a half years ago I knew only one America – an America that gave me an equal chance in the struggle for life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. If I were asked then – “What does America mean to you?” – I would answer without hesitation and with all sincerity – “America means freedom, equality, security, and justice.”

The other night, while I was preparing for this speech, I asked myself this same question – “What does America mean to you?” I hesitated – I was not sure of my answer. I wondered if America still means and will mean freedom, equality, security, and justice when some of its citizens were segregated, discriminated against, and treated so unfairly. I knew I was not the only American seeking an answer.

Marion Konishi delivered the valedictory at Amache graduation in 1943. She described herself as embittered but sought hope. “Can we, the graduating class of Amache Senior High School, still believe that America means freedom, equality, security, and justice? … Yes, with all our hearts, because in that faith, in that hope, is my future, our future, and the world’s future.”

Most visibly, the Amache Preservation Society has led reconstruction and restoration of the Amache cemetery, a 100-foot-tall water tower, a guard tower, barracks, and a recreation center. Visitors may take self-guided tours of Amache, with information provided at kiosks and on interpretive signs. During summertime, several students from Hopper’s Amache history class do maintenance work and provide tours and presentations for visitors.

Brandon Gonzales, a senior and standout athlete at Granada School, worked on upkeep at Camp Amache last summer. That included mowing the lawn at the quiet cemetery that memorializes about 120 people who died at the prison camp.

“I’m a lot more solemn here,” Gonzales said, as he walked through the irrigated oasis. “It’s peaceful in the mornings, and the knowledge I have of Amache hits me more intensely because people I’ve learned about are remembered here.”

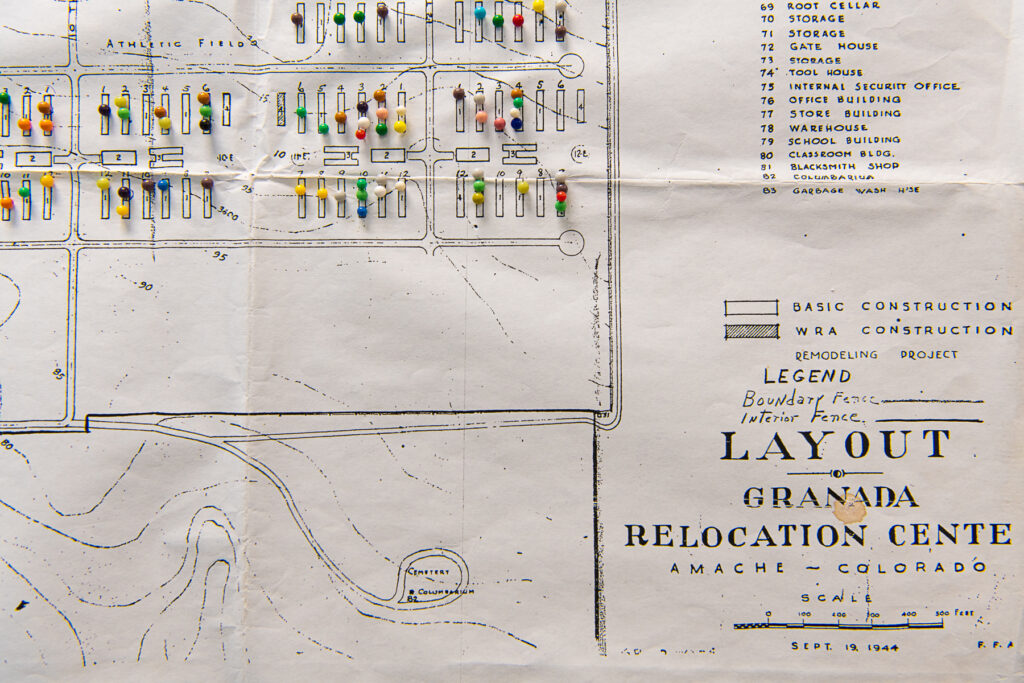

Visitors to the Amache Museum have used straight pins to mark a map of the barracks where they lived.

Gonzales and other students have been especially moved by the stories of nearly 1,000 young men and women who were imprisoned at Amache, yet volunteered for U.S. military service during World War II. Of those, 31 died in service. Their sacrifices came after the War Relocation Authority demanded that incarcerated Japanese Americans complete “loyalty questionnaires.” Among other questions, the forms asked about willingness to serve in the military. Respondents deemed “disloyal” were separated from their families and shipped to a prison camp in California. In this way, the authority pressed incarcerees to answer a call of duty to the very nation that detained them.

“We can’t forget their sacrifice and what they went through because they enlisted to fight in a war they were unfairly incarcerated for,” Gonzales said, as he led a tour of Amache.

“They showed loyalty to a country that wasn’t loyal to them,” agreed Grasmick, who joined the tour.

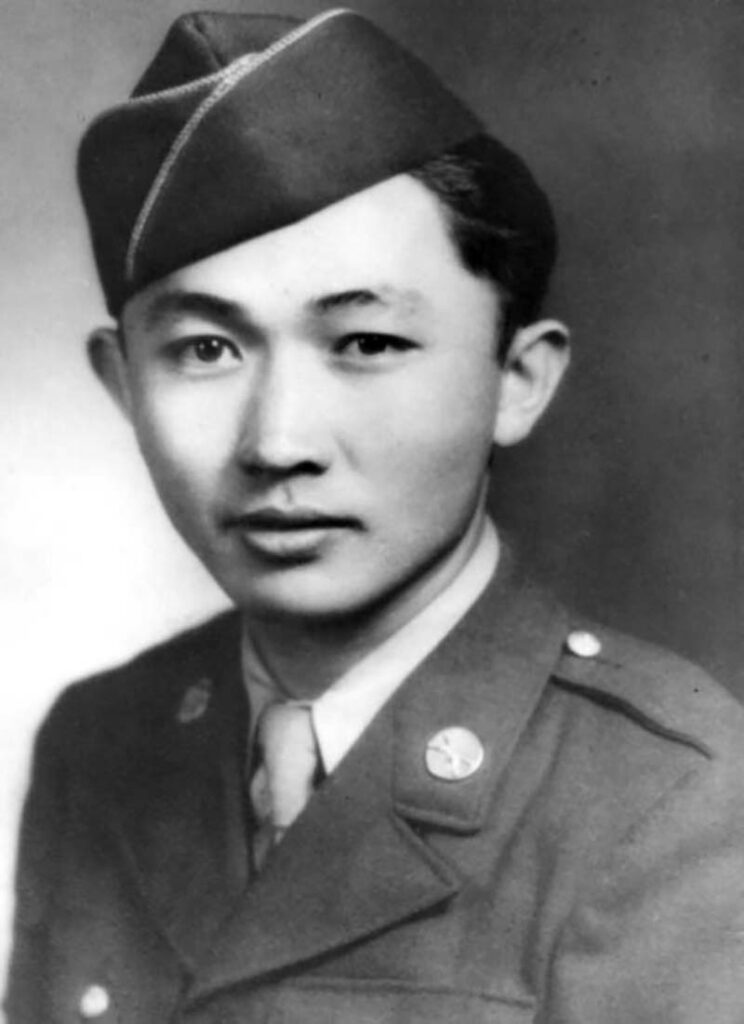

Kiyoshi Muranaga was held at Amache, joined the U.S. Army, and was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, the military’s highest award, for heroism in action in Italy.

Pfc. Kiyoshi Muranaga embodied that idea. He joined the U.S. Army in 1943, while being held with his family at Camp Amache. Muranaga was assigned to the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a segregated Japanese American unit. The 442nd is the most decorated U.S. military unit in history for its size and length of service. This is notable, according to the National WWII Museum, because “Japanese Americans faced two wars during World War II – war against the Axis powers and war against racism back home.”

In June 1944, Muranaga died in Italy as he singlehandedly manned a mortar weapon to protect his company during frontline combat. Muranaga was 22 years old. He was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, one of about 20 Japanese American soldiers to receive the U.S. military’s highest decoration.

“It takes a lot of courage to serve for a country that couldn’t care less about you, while at the same time your family is incarcerated behind barbed wire,” Grasmick said. “It tells you a lot about the pride of the Japanese Americans who were here.”

Photo at top: Sunrise reveals the reconstructed water tower and a guard tower at Camp Amache, a newly designated National Historic Site. It is off U.S. 50, on the outskirts of Granada in southeastern Colorado. The site is open to the public for self-guided tours. For information, visit amache.org.

SHARE