TOUGH TALK

Freedom of expression and its modern complexities

By Coleman Cornelius | Jan. 3, 2024

“Let me keep this simple: A Nazi is a Nazi is a Nazi.”

It was a remarkable line in a February 2018 email sent to the Colorado State University community from Tony Frank, who was campus president at the time and now is chancellor of the CSU System. The email was prompted by anti-immigration flyers posted on campus and attributed to the Traditionalist Worker Party, a neo-Nazi group that had helped organize Unite the Right, the rally that erupted into a deadly riot in Charlottesville, Virginia, just six months earlier. When the flyers surfaced, Frank saw the potential for violence; he alerted campus with a message that pointedly identified the group’s racist views and expressed solidarity with others who believed, “There is no place for such hate at Colorado State.”

The incident soon grew emblematic of First Amendment complexities that regularly arise on college campuses nationwide. These days, free expression is among the most fraught issues in higher education because students, faculty, and administrators are challenged to understand and uphold a pillar of U.S. democracy – while also improving the learning environment for historically marginalized students, who are most often targeted by hateful messages.

In September 2019, CSU students used their First Amendment rights to lead a protest march to draw attention to incidents of racial bias and to demand an improved learning environment for students of color. Photo: John Eisele / Colorado State University.

The commitments can seem at odds, Erwin Chemerinsky, a constitutional law authority, writes in his 2017 book, Free Speech on Campus. “Where should we draw the line between protecting free speech on college campuses and protecting an inclusive learning environment? Hardly a week goes by without new tensions around this question,” he writes in the book’s opening pages.

In this balancing act, higher education leaders must find ways to both staunchly defend the First Amendment while also boosting student safety and success, Frank recently said. “The greatest threat to the long-term future and health of colleges and universities appears to be in turning our backs on free speech,” he said. “The trick, it seems to me, is in providing learning environments in which to discuss any idea – even those that seem unsafe – and also in fostering an attitude that embraces that learning opportunity and engages the ideas in ways that will serve society well outside the college campus.”

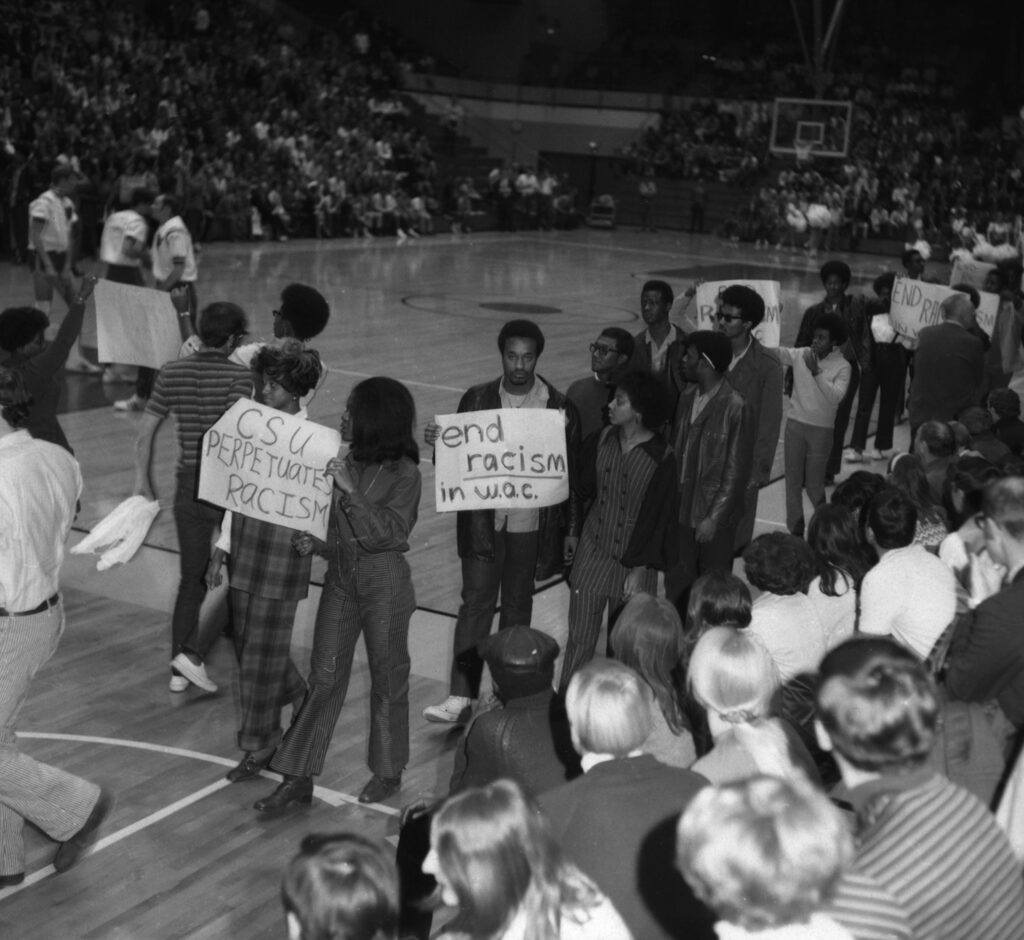

Members of the Black Student Alliance and Mexican-American Committee for Equality demonstrate in 1969 for equal access to higher education at CSU. Photography: CSU Libraries, Archives & Special Collections.

To that end, CSU leaders have adopted, reviewed, and refined policies and programs to support both First Amendment rights and students who feel harmed by offensive speech. Many of these efforts are housed in CSU’s Division of Student Affairs and Office for Inclusive Excellence. The university also has published a primer on free expression on campus. On March 25, a panel of experts will discuss central concepts, describe legal precedents, and help students, faculty, and staff navigate complexities. The panel is part of Colorado State’s thematic year of Democracy and Civic Engagement and comes at the start of an election year that is almost sure to spark animosity from all corners.

Yet, as CSU leaders and others have found, it is nearly impossible to anticipate all the campus incidents that will challenge obligations to both the First Amendment and student success. The university has annually received more than 200 reports of incidents allegedly motivated by prejudice, with the vast majority based on speech and writing related to race and gender. Most incidents have been protected as free expression, said Shannon Archibeque-Engle, associate vice president in CSU’s Office for Inclusive Excellence.

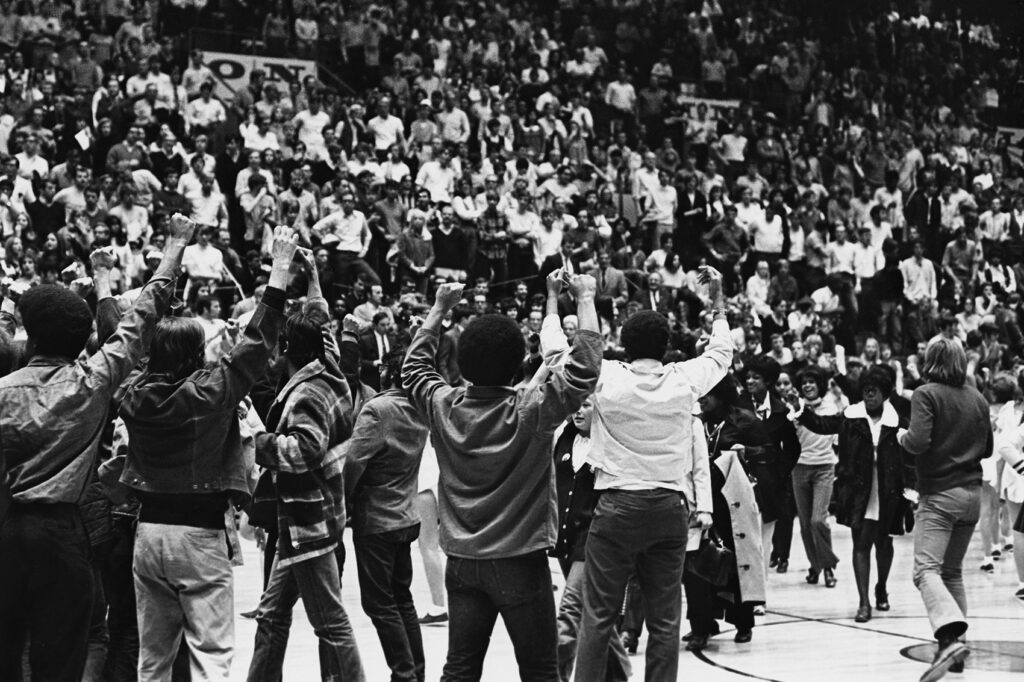

Left: Racial justice is the theme of a 1970 protest in Moby Gym. Right: CSU students join a Black Lives Matter protest in 2020. Photography: Colorado State University and CSU Libraries, Archives & Special Collections.

Top: Racial justice is the theme of a 1970 protest in Moby Gym. Bottom: CSU students join a Black Lives Matter protest in 2020. Photography: Colorado State University and CSU Libraries, Archives & Special Collections.

The flyers, an example of those incidents, chilled and enraged many in the campus community because they were part of a well-documented rise in nationwide white supremacist propaganda that reached an all-time high in 2022, according to the Anti-Defamation League’s Center on Extremism. These incidents have included distribution of racist, antisemitic, and anti-LGBTQ flyers, banners, posters, and graffiti intended to recruit neo-Nazis, provoke fear in minoritized communities, normalize intolerance, and foster a climate of vitriol and violence, scholars of political violence say. The rise in propaganda has coincided with a surge in reported nationwide hate crimes, or those motivated by bias toward race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, gender identity, and other factors, according to the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The problem has intensified since the start of the war in Gaza.

“It’s not just talk – this kind of hate narrative has real impact,” said Anarely Marquez-Gomez, who was a student majoring in political science and ethnic studies when the anti-immigration flyers were posted at CSU. For her, the threat was palpable: She was a “dreamer” who, at age 6, immigrated to the United States from Mexico with her family. Her residency was protected by the federal Deferred Action on Childhood Arrivals program, yet that protection seemed precarious – more so because of campus hate and bias incidents, including the flyers. “I remember at that time, we were just in survival mode,” she said. “It’s hard to learn when you’re in survival mode.”

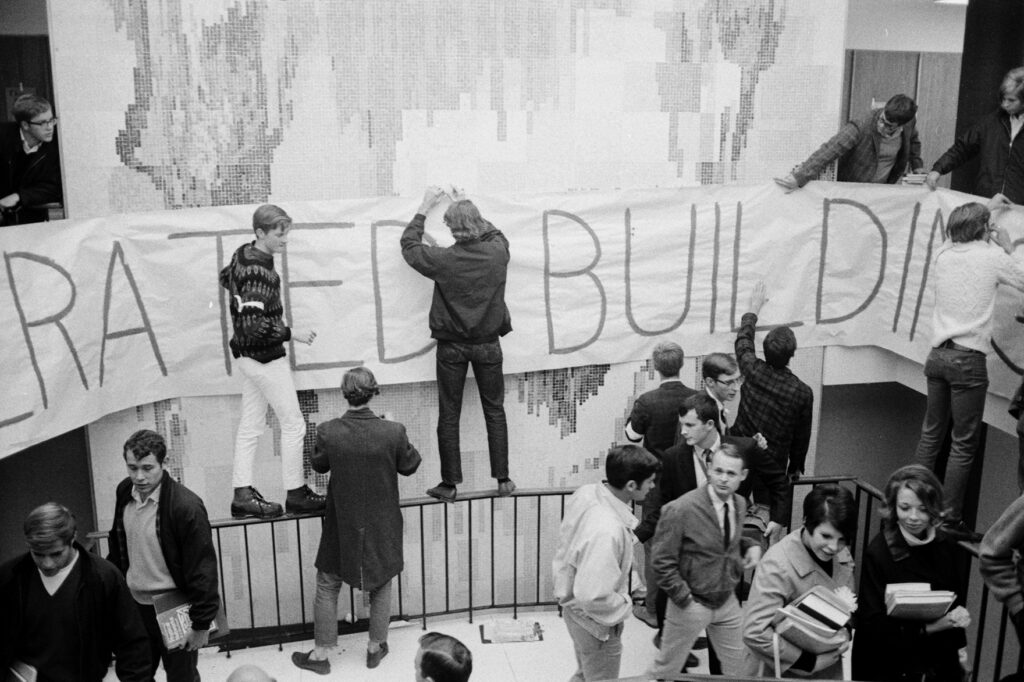

In 1968, students clamor for beer sales at the Lory Student Center as a step toward “liberating” the center from administrative control. Photography: Colorado State University and CSU Libraries, Archives & Special Collections.

MARQUEZ-GOMEZ, WHO GRADUATED in 2019, was a member of the President’s Multicultural Student Advisory Committee when the propaganda appeared. In response to that incident and others – including a crepe-paper noose in a residence hall, swastikas on a whiteboard, and preachers using the free-speech zone at the Lory Student Center Plaza to rail against queer students – the committee helped organize a campus rally called CSUnite to demonstrate commitment to an inclusive campus. “The goal was to take a stand, to send a message that ‘There’s a community here for you,’” said Marquez-Gomez, a speaker at the event. “The biggest way to counter hate is with grassroots activism.”

Students with diverse backgrounds, while advocating for campus cultures that ensure safety and allow them to thrive, often demand that universities sharpen student codes of conduct to prohibit racially biased and discriminatory expression, Chemerinsky writes. Yet, the First Amendment in most cases bars public colleges and universities from quashing objectionable speech or more severely punishing those who utter it, scholars say.

The dilemma has been more pronounced in recent years, in part because campuses are growing more diverse. Linked to that shift, public colleges and universities have grown more attuned to the imperative of educational equity baked into their missions. In particular, land-grant universities such as Colorado State were designed to deliver higher education to any student – from any background – with the talent and motivation to earn a college degree. And it is not enough to open doors, CSU leaders say. To deliver for the state it serves, a public university must seek to ensure all students succeed in their studies and graduate prepared for careers and civic life.

College is a time to be exposed to new ideas, to different ways of viewing an issue, to challenging ways of thinking. We don’t expect that our students will agree with all the new ideas and views that they are presented, or that other people will become converts to their thinking. But we do believe a university should model listening, questioning, and respectful disagreement, and that our students should come away knowing that they have a responsibility to protect the ability of others to speak their minds so that others, in turn, will protect theirs.”

— Tony Frank, chancellor, Colorado State University System

The issues gain gravity because college retention and graduation rates are notably lower for students of color than for white students, data from the U.S. Department of Education show.

“If we want students to enroll in our majors and succeed, we need to be as inclusive and welcoming as we can. Changing demographics necessitate it. This is who our constituents are, so the question is, ‘How do we do that while respecting the First Amendment?’” said Ria Vigil, assistant vice president in CSU’s Office for Inclusive Excellence. Vigil often works with professors to create classroom management plans that encourage diverse viewpoints while ensuring conflict is constructive. “I understand why people want to limit what other people say,” Vigil said. “But to want to limit speech, in the arc of history, is shortsighted. Free speech allowed the civil rights movement to happen.”

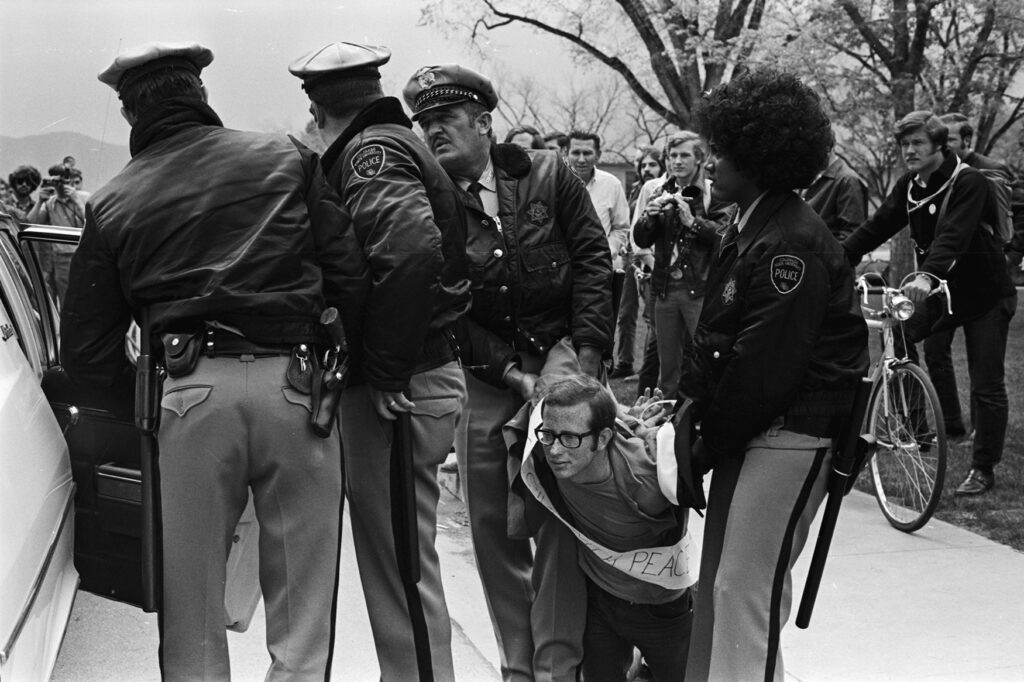

Clockwise from top left: Black students call for racial justice at a CSU basketball game in 1970; the same theme is the focus of a Black Lives Matter march in 2020; students in 1969 protest recruitment efforts of Dow Chemical Company on campus, based on the company’s production of napalm used in the Vietnam War; the CSUnite rally in 2018 stresses that CSU is “No Place 4 H8.” Photography: Colorado State University and CSU Libraries, Archives & Special Collections.

From top: Black students call for racial justice at a CSU basketball game in 1970; the CSUnite rally in 2018 stresses that CSU is “No Place 4 H8;” a Black Lives Matter march in 2020; students in 1969 protest recruitment efforts of Dow Chemical Company on campus, based on the company’s production of napalm used in the Vietnam War. Photography: Colorado State University and CSU Libraries, Archives & Special Collections.

IN FACT, THE FIRST AMENDMENT prevents public institutions – including public colleges and universities – from impinging on free expression, U.S. Supreme Court rulings have established. Public colleges and universities are government actors in the eyes of the First Amendment and must heed the bounds of protected expression.

Additionally, hate speech is often protected free speech: “In the public square, the First Amendment rightly protects expression that is vile, hateful, deliberately provocative, poorly argued, and even patently untrue,” according to “Campus Free Expression: A New Roadmap,” a report issued in 2021 by the Bipartisan Policy Center.

Left: A peace protestor is arrested after illegally occupying a campus building. Right: Students pay tribute to the Black Panther Party. Photography: Colorado State University and CSU Libraries, Archives & Special Collections.

Top: A peace protestor is arrested after illegally occupying a campus building. Bottom: Students pay tribute to the Black Panther Party. Photography: Colorado State University and CSU Libraries, Archives & Special Collections.

In the case of the flyers at CSU, there were further wrinkles. The racist propaganda piggybacked on a visit to CSU by conservative activist Charlie Kirk, founder of the nationwide student organization Turning Point USA. During his talk, Kirk renounced white nationalists. “That BS they’re trying to say out there, it’s not who we are, it’s not what we believe, it’s not what Turning Point believes,” he said at the presentation, which was invited by the organization’s CSU chapter. But the propagandists had effectively used Turning Point’s well-publicized public event to raise their own profile and create a clamor: Dozens of protestors and counter-protestors demonstrated outside the Lory Student Center, where Kirk spoke. As the evening wore on, a group of people wearing skull-emblazoned masks and carrying bats and shields appeared at the demonstration and chanted Nazi slogans, according to news reports. Police broke up the crowd to avoid violence; no one was injured or arrested.

But the incident didn’t end there. A coalition called Students Against White Supremacy petitioned to disband the campus chapter of Turning Point USA, claiming it promoted a toxic climate. University officials said student organizations may be disciplined only if they violate policies, and the Turning Point chapter had not.

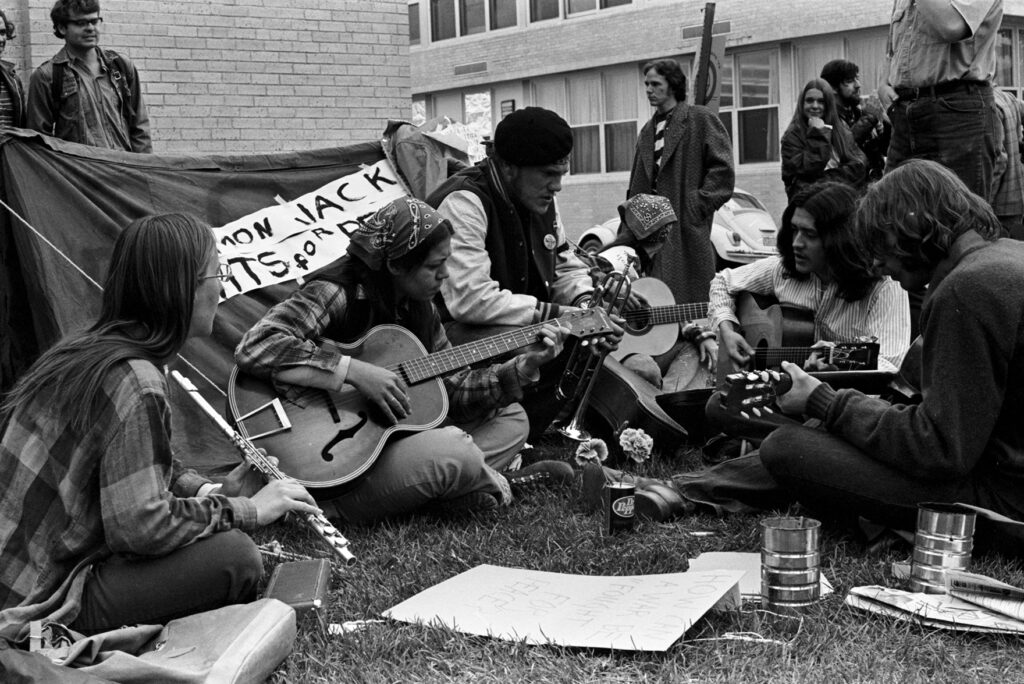

Left: In 1974, a student speaks from the Stump, which has anchored the free speech zone on the Lory Student Center Plaza for 60 years. Right: CSU students play music during a 1972 peace demonstration against the Vietnam War. Photography: Colorado State University and CSU Libraries, Archives & Special Collections.

Top: In 1974, a student speaks from the Stump, which has anchored the free speech zone on the Lory Student Center Plaza for 60 years. Bottom: CSU students play music during a 1972 peace demonstration against the Vietnam War. Photography: Colorado State University and CSU Libraries, Archives & Special Collections.

Responding to harmful speech, “[T]he remedy to be applied is more speech, not enforced silence,” former U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis famously wrote in a case opinion in 1927. Karrin Vasby Anderson, a CSU professor of communication studies, teaches students in her political communication course to consider a twist on that idea: better ways of speaking. More effective than angry monologues are deliberative conversations, personal storytelling to illuminate opinions, avoidance of scapegoating – and listening, a skill “as important as speaking,” she said.

“The solution to bad speech isn’t more speech. It’s better ways of speaking. That’s what we can offer to our students and our community. These are habits that produce healthy, vibrant democracies,” said Vasby Anderson, who is among the CSU professors teaching aspects of the First Amendment.

Veterans march in favor of the Vietnam War, reflecting a common sentiment in the city of Fort Collins at the time. Photography: CSU Libraries, Archives & Special Collections.

JACOB GINSBERG-MARGO, a political science major and former president of the CSU chapter of College Republicans, said he appreciates the ability to hear and express a variety of viewpoints on campus. “Dialogue, especially dialogue when you disagree with someone, is a way of sharpening your thinking and getting better,” he said. For instance, his political differences with liberal students have prompted Ginsberg-Margo to research critical race theory and other topics. “Disagreements,” he said, “push people to learn more and speak better.”

Mike Ellis, a leader in the CSU Division of Student Affairs and executive director of the Lory Student Center, is often in the middle of free expression controversies on campus. The student center is a key speaking venue, and its Plaza is a free-speech zone that routinely attracts fire-and-brimstone preachers and political provocateurs, among others. Intense emotion often results, and Ellis is there fielding complaints and encouraging students to express reasoned opposition, to act as allies, or to simply ignore offensive messages.

“We have a duty and a responsibility to uphold the First Amendment. But, as individuals and as an institution, we also have rights through the Constitution to express our own values,” Ellis said he regularly explains. “I love it,” he added of the educational process. “We should be helping our students find their voices.”

We have the highest unemployment rate in the United States. Sixty percent of our youth never finish high school. … Scholarship agencies, which are set up for us, are run by non-Indian boards. Many of our people are never well because they do not have money to buy the food they need to be healthy. I hope we have not forgotten how to be mad. We have accepted defeat too long.”

— Native American student B.J. Goodluck, who exercised a First Amendment right by demanding that CSU provide educational opportunities for more students of color, April 10, 1969

BORN AND RAISED in the segregated South, Blanche Hughes, vice president of student affairs, is a Black woman who said, “Having neo-Nazis on campus rocked my world.” Yet, she also understands the importance of free expression, having attended college on the heels of the civil rights movement and having grown up with parents who, for much of their adult lives, did not have the right to vote. She frequently provides this historical perspective when discussing free expression on campus.

“We were not allowed the same rights because of the color of our skin, and part of the civil rights movement was having free speech rights to protest injustice. People fought and died in this country so we could have those rights,” Hughes said. “Freedom of speech allows people to be cruel and hurtful on campus, and students want us to stop that. But how do you decide what can and can’t be said? That’s not the answer. The answer is using freedom of speech to improve us.”

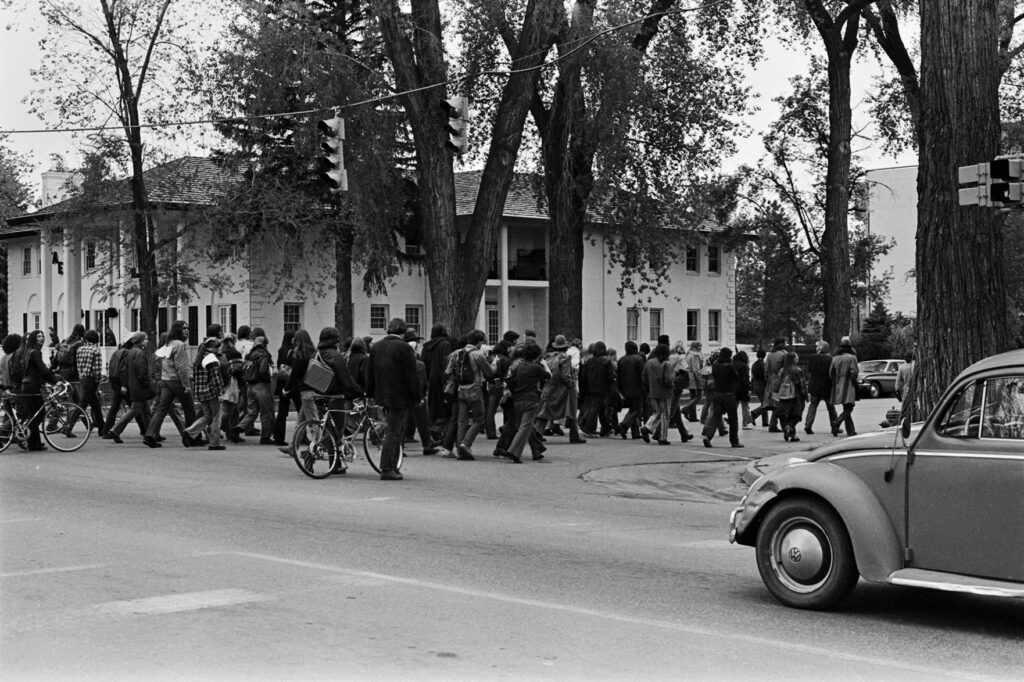

Left: CSU students join an anti-war march to Fort Collins City Hall in 1972. Right: Students lead the CSUnite rally in 2018 to underscore the university’s Principles of Community, which are inclusion, integrity, respect, service, and social justice. Photography: Colorado State University and CSU Libraries, Archives & Special Collections.

Top: CSU students join an anti-war march to Fort Collins City Hall in 1972. Bottom: Students lead the CSUnite rally in 2018 to underscore the university’s Principles of Community, which are inclusion, integrity, respect, service, and social justice. Photography: Colorado State University and CSU Libraries, Archives & Special Collections.

The Bipartisan Policy Center’s “Campus Free Expression” report likewise advocates changing the paradigm to better bridge campus free speech and inclusivity. “While not ignoring that there may be expression that is hurtful,” it says, “we believe profoundly that free expression is an essential means to an inclusive campus in addition to being essential to higher education’s academic and civic missions.”

Frank put it this way: “College is a time to be exposed to new ideas, to different ways of viewing an issue, to challenging ways of thinking,” he said. “We don’t expect that our students will agree with all the new ideas and views that they are presented, or that other people will become converts to their thinking. But we do believe a university should model listening, questioning, and respectful disagreement, and that our students should come away knowing that they have a responsibility to protect the ability of others to speak their minds so that others will, in turn, protect theirs.”

Photo at top: In 1969, CSU student Manuel Ramos, of the Mexican-American Committee for Equality, center, joins leaders of the Black Student Alliance to call for admission of more students of color at CSU. The students exercised their First Amendment rights of assembly, speech, and petition to push for equal access to higher education. Reporters covering the event exercised rights of the press. Photo: CSU Libraries, Archives & Special Collections.

SHARE