HEAT WAVE

Firing up Pueblo chile from seed to supper

By Coleman Cornelius

Photography by Ben P. Ward, Colorado State University

March 15, 2021

Pop quiz: What kind of hamburger do you eat with a spoon?

Answer: A Pueblo Slopper, of course.

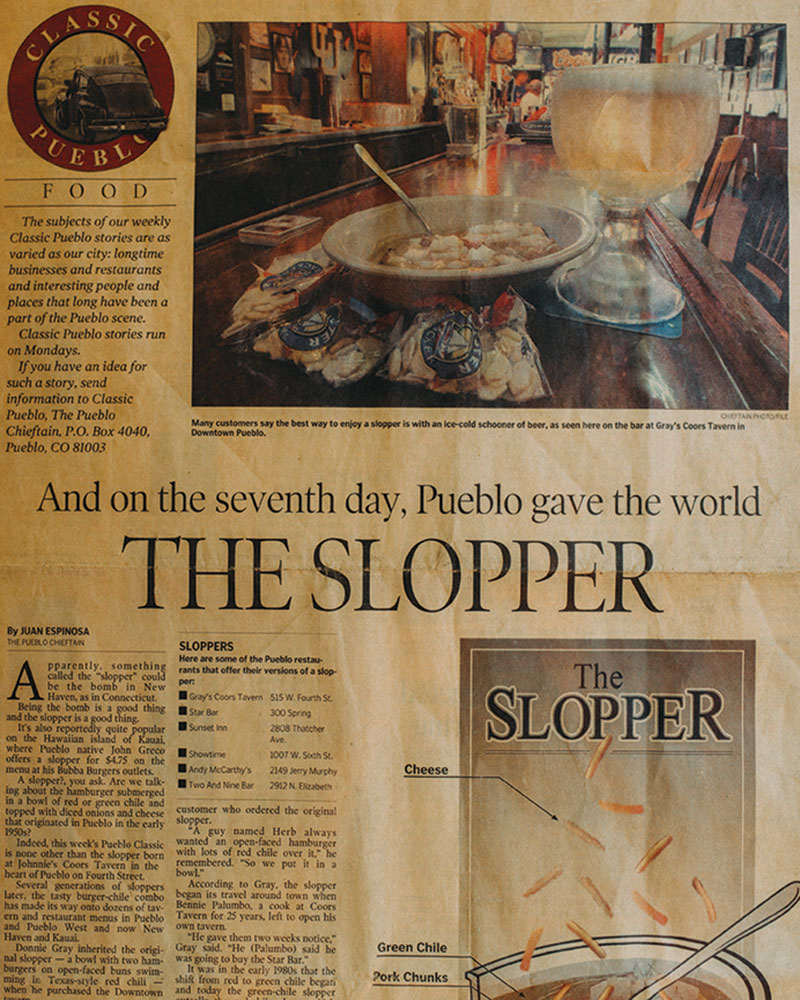

ACCORDING TO LORE, the southern Colorado specialty was concocted at Johnnie’s Coors Tavern in downtown Pueblo around 1950, when a regular asked pub owner Johnnie Greco for a burger smothered in chili sauce. The customer was Herb Casebeer, a nearby shop owner. He often joined the local clientele, mostly railyard workers, to order one (or all) of the tavern’s three menu items. Those days, the pub served only Coors beer, burgers, and chili by the bowl. This time, Herb wanted something else: a burger-and-chili combo. Not just a dollop, you can hear him saying; really slop it on.

The result might have been a bit of culinary comeuppance on Johnnie’s part. As in, “You said you wanted a lot.” In fact, the burger now known as the Pueblo Slopper is delivered literally swimming in a sauce of Pueblo green chile and other ingredients. It’s served topped with chopped onion and shredded cheese. In a bowl. With a spoon. The pub that originated the Slopper – now Gray’s Coors Tavern, after a change in ownership – references and explains the oddball burger with its motto, “Covering our buns in chili since 1950.”

The iconic Gray’s Coors Tavern is co-owned and managed by Carrie Fetty, a CSU Pueblo alumna (above left). She runs a family business that for years has touted Pueblo chile.

The iconic Gray’s Coors Tavern is co-owned and managed by Carrie Fetty, a CSU Pueblo alumna (top). She runs a family business that for years has touted Pueblo chile.

When you visit Pueblo for the first time, count on being asked: “Have you tried a Slopper?” (Truly, it would be hard not to, since versions are found across the city.) And if you’re a first-timer at Gray’s Coors Tavern, the staff will celebrate your rite of passage, as tavern co-owner Carrie Fetty did when a Colorado State University photographer took his inaugural chomp last fall. “Ladies and gentlemen!” Fetty called out to tavern patrons, while loudly clanging a bell bolted over the bar. “We’ve got Ben from Lakewood here, and he is no longer a Slopper virgin!”

The ruckus is more than a gimmick: It’s an initiation into the world of Pueblo chile. Here in Pueblo, green chile is a cultural touchstone and a source of deep community pride. It symbolizes the community’s history, its diverse cultural heritage, and its agricultural foundation, carried forward by Italians and other immigrants who started arriving in the late 1800s to work in Pueblo’s mighty steel and railroad industries and then began farming in the irrigated Arkansas River Valley.

“Chile brings people together around the dinner table, but on a macro level it brings the community together. It shows who we are as a people, who we are as a culture. It’s part of our identity,” said Steven Trujillo, a CSU Pueblo graduate honored as the university’s 2019 Distinguished Young Alumnus. Born and raised in Pueblo, he is president and CEO of the city’s Latino Chamber of Commerce.

DURING THE PAST FIVE YEARS, the crop’s visibility has flared, as scientists, farmers, food purveyors, and community leaders have joined forces to more broadly market distinctive, locally developed pepper varieties branded as “Pueblo chile.” It’s a hot take on economic development – connecting a small but potent crop to surging interest in locally grown food and the power of place in its marketing. The formula has fueled other Colorado favorites, including Olathe sweet corn, Palisade peaches, and Rocky Ford cantaloupe, another mainstay of the Arkansas Valley.

Many of the tastemakers touting Pueblo chile are alumni and employees of Colorado State University and CSU Pueblo. Their work is firing up the Pueblo chile industry from seed to supper. Sure, there’s a certain state just to the south (ahem, New Mexico) that dominates the chile market (i.e., “Chile Capital of the World”).

Yet, advocates see plenty of room in the marketplace, especially given the area’s seemingly insatiable appetite for Pueblo chile. Around here, chile is served at breakfast, lunch, and dinner; in eggs, on burgers, in margaritas, on pizza. By the cup and by the bowl. Ladled generously over every beef and bean burrito.

“There’s no place that has green chile like the chile from Pueblo, Colorado. I don’t care what anyone says,” said Carolyn Gray, who co-owns Gray’s Coors Tavern with her husband and children.

“Amen,” Fetty, her daughter, agreed.

Fetty was a kid when her family took over the iconic tavern; she waitressed as a teenager, slinging Sloppers up and down the 57-foot bar and adjacent shotgun dining room. She graduated from CSU Pueblo in 1994 with a bachelor’s degree in psychology and a teaching certificate, then taught first grade in her hometown for 23 years. Instead of retiring, she started a second career: Fetty and her two brothers bought into the family business in 2018, and Fetty, as tavern manager, replaced her cousin Donny Gray as the face of the place that originated the Pueblo Slopper.

Now, the tavern serves about 400 Sloppers a day – typically 200 by 2 o’clock on a busy Friday. Demand has been steady during much of the COVID-19 pandemic. Some Denver residents have even driven more than 100 miles in their motorhomes for takeout Sloppers, eaten in the socially distanced safety of their RVs. “We’re happy they could come get that comfort food,” Fetty said.

Since the 1500s, chile has been cultivated in what we now know as the Southwestern United States; it has been a staple crop in the Arkansas Valley east of Pueblo for decades, if not centuries. Although its start in southern Colorado is murky, chile was well-established at Pueblo truck farms by the mid-1900s. Chile is a small part of Colorado’s agricultural industry, but holds potential as a high-value specialty crop rooted in community culture.

In September 2010, her pub helped plant the seed for today’s Pueblo chile marketing campaign. That’s when Discovery’s Travel Channel aired an episode of Food Wars, pitting Sloppers from Gray’s Coors Tavern against those from crosstown competitor Sunset Inn. The show staged a blind taste test amid a crowd of placard-waving Slopper fanatics; adding local flair, Miss Rodeo Colorado was among the blindfolded judges, wearing her perfectly shaped cowboy hat, turquoise jewelry, and sash. With breathless onlookers, Sunset Inn won the battle in a final tie-breaking vote, prompting inn owner, Chuck Chavez, to declare: “I never dreamed something like this would happen.”

Indeed, the show stoked a craving for Sloppers and Pueblo chile: Customers arrived at both restaurants in droves, from across the country and even abroad. Although the Food Wars host called the two joints “sworn Slopper enemies,” their owners are actually friends. Even as Fetty described the TV segment’s impact on her business, Chavez sat at her bar with a couple of buddies.

“We love Chuck. He comes to our place, and we go to his. Everything here is about supporting our community,” Fetty said. “Pueblo chile is part of that. We’re proud that we can support Pueblo farmers, and they support us.”

After Food Wars, local chile got another bump in the ratings when former President Barack Obama stopped at Romero’s Café and Catering during a campaign swing through Colorado in 2012. The café is another fixture on the Pueblo chile scene, and the former president made a politic choice with his breakfast order – enchiladas tejanas with chorizo and green chile. He was impressed: “I’m going to work with the White House chefs to see if we can figure out some of the secrets here,” Obama said. The praise was widely reportedly in news media, again boosting the stature of Pueblo chile.

I’m going to work with the White House chefs to see if we can figure out some of the secrets here.

— Former President Barack Obama

The notoriety might be fairly new, but the crop is not. By most estimates, chile arrived in the region 400 to 500 years ago, after Spanish conquerors discovered varieties of Capsicum annuum skillfully cultivated by the Aztec people of present-day Mexico. The Spanish conquest – along with trade and seed-dispersing birds – carried chile cultivars north, where they took root with indigenous people and colonizers alike, according to The Chile Chronicles: Tales of a New Mexico Harvest, by Carmella Padilla. It wasn’t long before chile was an essential crop across the Southwest, where it thrives in hot days and cool nights.

Now, green chile is commercially harvested by the ton and often is sold fresh, then roasted for complex flavor, and peeled and de-seeded for cooking. When frozen, canned, or otherwise processed, it’s ready for year-round use. Some plant varieties produce red fruit, often slightly sweeter, earthy, and dried – traditionally collected in gorgeous, hanging ristras.

From these basics come all manner of uses and regionally idiosyncratic recipes. In Pueblo, for instance, order green chile at a restaurant, and you might get a dish made with roasted and chopped green chile, crushed tomatoes, onion, garlic, pork, and broth. By contrast, green chile served in northern New Mexico, just a couple hundred miles away, is often closer to a single-ingredient preparation – mostly roasted chile. Adding confusion, either rendition might be an entrée or a sauce, as is the green chile covering Pueblo Sloppers. Even the spelling varies: “chile” among botanically inclined purists and “chili” among those influenced by Texas and its trademark stew, which just happens to contain … dried red chile. (In this story, we use spellings preferred by the people and businesses highlighted.)

Left: Gray’s Coors Tavern originated the famed Pueblo Slopper. Right: The Walter Brewing Company makes three chile lagers and is among many Pueblo businesses selling products made with locally grown peppers.

Top: Gray’s Coors Tavern originated the famed Pueblo Slopper. Bottom: The Walter Brewing Company makes three chile lagers and is among many Pueblo businesses selling products made with locally grown peppers.

Spell it as you wish, but find chile everywhere around Pueblo – even in craft beer. The Walter Brewing Company, operating in a historic brewery near Pueblo’s downtown river walk, makes three specialty lagers using locally grown green and red chile. Its use echoes the early days of brewing, when spices, herbs, and fruit were commonly used in beer making. Walter’s Pueblo Chile Beer is the best known of the brewery’s zesty lagers and is sold in more than 300 retail outlets across Colorado, in cans emblazoned with green chile graphics.

“Walter’s Beer is an excellent ambassador for Pueblo chile, to help take it to the level the community would like to see,” said Mia Sanchez, a brewery co-owner and manager, as she poured piquant tasters in the taproom. She graduated from Colorado State University in 2000 with a bachelor’s degree in apparel and merchandising.

Several years ago, Sanchez and her husband, Andy, joined a group of investors to buy the historic brewery, refurbish the old building, and reignite Walter’s Beer, which dates to 1889 in Pueblo and languished when the brewery closed in 1975. The couple are native Puebloans, and they have forebears who farmed and worked at the brewery. So making beer with Pueblo chile is a way to reach a market niche while honoring both personal and city history, said Andy Sanchez, who studied art and business at CSU Pueblo and graduated with a bachelor’s degree 1998.

“A brewery is a mirror of the local flavor of the community,” Sanchez observed. He earlier worked in product branding and as development director for the CSU Pueblo Foundation; he became a prominent community booster as board chair of the Greater Pueblo Chamber of Commerce. The brewery brings it all together. “We’ve got beer that encapsulates many aspects of our lives and of Pueblo, and that makes it exciting,” Sanchez said.

The Walter Brewing Company proprietors Mia and Andy Sanchez are graduates of CSU and CSU Pueblo, respectively.

Fittingly, Walter’s Pueblo Chile Beer debuted at the preeminent showcase for locally grown peppers: the Pueblo Chile & Frijoles Festival.

A project of the Greater Pueblo Chamber of Commerce, the harvest festival started in 1994 as a downtown farmers market, an early effort to promote Pueblo chile. It has blossomed into an annual community celebration and an economically vital event – awarded as an outstanding community initiative during the 2019 Colorado Governor’s Tourism Conference.

The festival was downsized last year because of the pandemic. But it typically attracts 150,000 people each September for roasted green chile, pinto beans, and fresh produce from local farmers. There are cooking demonstrations, entertainers, salsa showdowns, jalapeño-eating contests, a Chihuahua parade, and vendors offering the centerpiece crop in every conceivable form, including green chile milkshakes. CSU Pueblo has been among the festival sponsors as it works to strengthen community ties.

The annual Pueblo Chile & Frijoles Festival has grown from a small farmers market into a marquee event that attracts some 150,000 people to downtown Pueblo each September. It is sponsored in part by CSU Pueblo. Photo: Visit Pueblo / Greater Pueblo Chamber of Commerce

The Pueblo Chile Growers Association, an arm of the Greater Pueblo Chamber of Commerce, has become a driving force behind the festival and officially leads the Pueblo chile campaign. The group’s strategies are straight out of a marketing playbook. Yet, its efforts are notable for joining people from different professional spheres to brand, elevate, and capitalize on a crop that, for years, has uniquely contributed to community identity.

In 2015, a handful of well-established chile farmers formed the association, a milestone for Pueblo chile. “The idea is that we could bring chile farmers together to collaborate for the greater good of the whole by clearly establishing the brand and marketing our product,” said Donielle Kitzman, who attended CSU Pueblo in the 1990s to study political science and communication. Kitzman provides administrative muscle for the Pueblo Chile Growers Association as its executive director; she connects the group to the broader business community in her related role as a vice president for the chamber of commerce.

“This can uplift the whole community – chile is the flag we can carry,” said Mike Bartolo, a widely admired CSU horticulturist who helped form the Pueblo Chile Growers Association. For years, Bartolo has managed the university’s Arkansas Valley Research Center in Rocky Ford, east of Pueblo, and he developed the distinctive chile varieties grown and sold as Pueblo chile. “We’ve got real potential to run with this,” he said of the marketing push. “All these different vectors with Pueblo chile are coming together, and it has some great energy.”

Left: Dominic DiSanti, founding president of the Pueblo Chile Growers Association. Center: Bryan Crites, association board member. Right: Kay Crites, Bryan’s mother, who, with her husband, raises chile seedlings for the area’s largest chile farmers.

Top: Dominic DiSanti, founding president of the Pueblo Chile Growers Association. Middle: Bryan Crites, association board member. Bottom: Kay Crites, Bryan’s mother, who, with her husband, raises chile seedlings for the area’s largest chile farmers.

In the five years since it formed, the growers association has focused on propelling sales in Metro Denver and across Colorado, using existing resources and an array of new communication efforts. The group trademarked its logo. Farmers have led harvest-season tours. And they persuaded the Colorado General Assembly to approve a vehicle license plate promoting Pueblo chile. The association also has worked with Colorado food processors – makers of cheese, hot sauce, salsa, sausage, spirits, tortillas – to use Pueblo chile.

The result is a notable uptick in fresh chile sales through the three main outlets growers rely on: restaurants and food processors, grocers, and direct-to-consumer farm stands. The association has not yet developed a mechanism to track overall sales volume. Even so, the group estimates that visitation to local farm stands has recently increased by about 30 percent as more people arrive seeking Pueblo chile, Kitzman said.

Another big step in 2015: Some Whole Foods stores in the Rocky Mountain region started seasonal sales of Pueblo chile, elbowing out chile from the area around Hatch, New Mexico. (Of course, stores in New Mexico stick with their own.)

The switch inflamed an interstate chile debate that rockets through social media and news outlets each harvest season. The governors of Colorado and New Mexico have even exchanged fiery rhetoric over the merits of green chile grown in their respective states.

Despite some orneriness, the publicity is good for business, Kitzman said. “We’ve seen a large growth in product utilization. With the chatter and the conversation, Pueblo chile has become more noticed,” she said, adding, “At the end of the day, we support farmers and the agricultural industry as a whole, even if we happen to like our chile better.”

Setting aside preferences, the contrast is clear: In 2019, New Mexico farmers planted a total of more than 9,000 acres of chile, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Colorado farmers plant perhaps 1,000 acres, virtually all in the Arkansas Valley east of Pueblo, Bartolo said.

Even in Colorado, chile is low on the list of commercial produce, based on acreage and sales. Statewide, more than 90,000 acres are planted in fruits and vegetables, known as specialty crops, with a total of about $485 million in sales, according to the Colorado Fruit & Vegetable Growers Association. The state’s most significant specialty crops include potatoes, onions, peaches, sweet corn, lettuce, and melons; potatoes, grown chiefly in southern Colorado’s San Luis Valley, lead the rest by far.

As harvest was underway last September, customers waited for bushels of chile to roast at DiSanti Farm Stand outside Pueblo.

YET, CHILE STANDS OUT for its market potential as a high-value crop, in part because of its community and cultural connections. That’s why farmers in the Pueblo Chile Growers Association focus attention on chile when, in the scheme of things, their primary concerns more often relate to labor shortages, water availability, and food safety.

“I think we’ve solidified ourselves as the chile-growing region in the state. Now, when you think chile in Colorado, you think Pueblo chile,” said Dominic DiSanti, a founder and the first president of the Pueblo Chile Growers Association. DiSanti is a former Boettcher Scholar at Colorado State University who graduated in 2009 with degrees in both agricultural business and animal science.

He’s a fourth-generation farmer whose family emigrated from Italy, and he runs DiSanti Farms with his mother, siblings, and wife, Jayme DiSanti, who attended CSU Pueblo. DiSanti Farms raises cattle, grain corn, hay, and 400 acres of vegetable crops, Pueblo chile among them. Like many Pueblo farms, it sits along U.S. 50 on a stretch of elevated plain known as St. Charles Mesa.

If water is life, then irrigation is the lifeblood of these farms. Here, crop production depends on irrigation water diverted from the Arkansas River and delivered by Bessemer Ditch. The waterway was completed in 1890 and is named for a steel-making process; it was principally financed by Colorado Coal & Iron Company, which evolved into the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company, the Pueblo steel giant that for a time was the state’s largest employer.

Pueblo chile symbolizes these interwoven community threads, and its successful marketing might aid the survival of family farms on the Mesa and elsewhere in the Arkansas Valley, DiSanti said. As he spoke last September, visitors thronged the DiSanti Farm Stand for bushels of green chile roasted on the spot. “One thing about our customers – they know good chile,” he said.

I think we've solidified ourselves as the chile-growing region in the state. Now, when you think chile in Colorado, you think Pueblo chile.

— Dominic DiSanti

Several miles east, 14 barrel roasters were cranking at Crites Produce, emitting the unmistakable aroma that is a clarion call for chile fans when summer turns to fall. Last September, Bryan Crites oversaw the bustle of chile harvesting in his fields, followed by roasting, chopping, bagging, and sales to thousands of regular folk and dozens of restaurants, including Gray’s Coors Tavern and Romero’s Café and Catering.

“This is where I figured out I like to make things grow,” said Crites, a board member of the Pueblo Chile Growers Association. He had just returned from the fields to his chile processing facility, adjacent to his boyhood home. As Crites arrived in a truck loaded with bushels of green chile, eight employees – plus his parents – were busy prepping orders for customer pickup.

Crites attended CSU Pueblo on a basketball scholarship in the mid-1990s and started farming in the community of Avondale after working for a decade as a local firefighter.

Chile is just part of the Crites Produce operation – but it gets the most attention. Earlier that week, Crites led a tour for Gov. Jared Polis and later marveled when Polis posted a photo of his lunch on social media. “That’s actually my chopped chiles on that sandwich,” Crites said with a grin, as he monitored reactions on his cellphone.

Bryan Crites (left), who attended CSU Pueblo, owns Crites Produce in Avondale, east of Pueblo. He harvests and processes chile with a crew of seasonal farmworkers, eight employees, and his family. Robert Phillips (right) works as the head chile roaster for Crites Produce each harvest season.

Bryan Crites (top), who attended CSU Pueblo, owns Crites Produce in Avondale, east of Pueblo. He harvests and processes chile with a crew of seasonal farmworkers, eight employees, and his family. Robert Phillips (bottom) works as the head chile roaster for Crites Produce each harvest season.

His farm, with 600 acres in crop production, began as an offshoot of his parents’ thriving greenhouse business. Along with annual flowers and vegetable starts, Kay and Gary Crites raise chile seedlings in their greenhouses; their buyers, some of the area’s largest chile farmers, rely on transplants to get a jump-start on the growing season.

During harvest, Kay Crites runs the business office, taking dozens of requests by phone each day. Most customers order their chile by the bushel, and Crites Produce offers processing that differentiates the farm from most others. Its chile comes mild, medium, hot, “XXHOT,” and roasted with or without garlic. It can be whole or de-stemmed; peeled or peeled and chopped; in big food-grade plastic bags, or vacuum-sealed in 1-pound bags; even fully processed and frozen. Prices range from $20 to $50 a bushel, depending on the treatment.

“Chile is a staple. It’s like flour and rice – you’ve got to have your chile,” Kay said, as she logged orders left by voicemail. Customers would later arrive from Pueblo, Metro Denver, mountain towns, and (brace yourself) northern New Mexico. Just outside the office, Robert Phillips manned the roasters, impervious to the pungent vapor. “My lungs are cooked,” he joked.

After loading a roaster with fresh green chile, Phillips rinsed the peppers with water from a high-pressure nozzle, lit a row of propane burners with a whoosh, and started the barrel turning over flames. Soon, chile skins began to blister, crackle, darken, and spark; a few minutes more, and Phillips stopped the roaster. He again blasted the chile with water, denuding the peppers of charred skins; now the roasted bushel was ready for next steps.

“When it’s not chile season, you miss it. People count down the days,” said Phillips, who met Bryan Crites when they competed in high school basketball around Pueblo.

Crites Produce grows many crops. Yet, its chile operation is distinctive for the variety of processing options offered after harvest – not only roasting, but peeling, bagging, chopping, and freezing.

As dusk neared, Crites drove with his 14-year-old daughter, Emily, to a chile field, where a crew of a dozen seasonal farmworkers had earlier moved methodically down furrows plucking peppers. Crites checked plants laden with chile and worried about a forecast of early snow that could threaten the crop.

“He’s a very hardworking man. That’s what he’s done his whole life,” Emily said of her dad, as she stood amid rows and rows of chile plants. “I’m very proud of him.”

Father and daughter later joined Kay and Gary Crites at the roasting shed for a dinner of takeout pizza from a Pueblo restaurant. It was topped with green chile from their own farm. “This is the rewarding part,” Bryan said, sipping a beer as the sun set. “I like being able to grow something that people enjoy.”

Mike Bartolo is a CSU alumnus and long-time manager of the Arkansas Valley Research Center in Rocky Ford. Over 30 years, he has developed the distinctive pepper varieties branded and marketed as Pueblo chile.

That enjoyment starts with chile seed. And that, in turn, starts with research scientist Mike Bartolo.

For 30 years, Bartolo has cultivated and analyzed chile at CSU’s Arkansas Valley Research Center and has shared his findings with area farmers. Chile has been his passion project, a sideline to countless studies of irrigation efficiency, pest management, soil health, and other issues central to sustainable farming practices.

It has been a labor-intensive approach to plant breeding: Sow chile seeds in farm ground, observe the plants and fruit produced, identify thick-walled peppers with superior flavor and heat, collect the seeds from those peppers. Repeat. Over the decades, Bartolo has made some 400 selections using this process. “It’s out of hand,” he said, laughing. “It might be some kind of sickness.”

His work has yielded three distinct chile varieties grown by area farmers – now branded and marketed as Pueblo chile. Tops among them is the Mosco chile, a hot, meaty pepper that is the most widely grown cultivar in the Arkansas Valley. Bartolo’s chile breeding also has produced the Giadone cultivar, a pungent pepper named for the late Pete Giadone, a well-known Pueblo farmer and chile advocate; and the Pueblo Popper, a round novelty chile that works well for stuffed pepper recipes. The strains grew from a landrace called Mirasol, Spanish for “look to the sun,” which refers to the fruit’s upward growth habit.

A busy harvest day draws to a close as dusk settles on the irrigated Arkansas Valley, one of Colorado’s key agricultural regions, which stretches across the Plains east of Pueblo.

Bartolo’s family story is familiar in Pueblo: He is the grandson of Italian immigrants who arrived to work in the steel industry and started farming on St. Charles Mesa; their surname, later shortened, was Bartolomucci. His family always grew chile, Bartolo said. He remembers it in his grandmother’s kitchen and at many meals and gatherings.

Near Bartolo’s family farm, his uncle Harry Mosco had a modest truck farm and grew chile, each year keeping seeds from desirable pods to sow for the next season’s crop. It is the exact process Bartolo has used to develop varieties branded as Pueblo chile.

After his uncle died, Bartolo inherited a small cloth sack of chile seed. It is marked “H87” – Harry’s chile seed from 1987. Harry didn’t live to plant the seed in 1988. But his nephew did. That dusty white bag of seed, weighing no more than a little paperback novel, launched Bartolo’s chile project. It launched an entire web of community effort to yield Pueblo chile.

“The farmers who came before us gave us an opportunity,” Bartolo said. “We’re building on their backs. We should never forget that.”

SHARE